Conferment of Master’s Degrees

| Conferment of Master’s Degrees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

Dating back to the Middle Ages, the conferment of master’s degrees is an academic occasion for those who have completed their master’s degree or doctorate to celebrate their achievement in a sophisticated setting. Participation in the conferment is the only way for the graduates to receive the right to use the symbols of their academic degrees: the wreath and ring of a master, or the hat and sword of a doctor. Most Finnish universities and many foreign ones only hold conferment ceremonies for doctors, but four Finnish universities also organise conferment ceremonies for masters. These four combine the ceremonies intended for doctors and masters, but the fact that masters are allowed to participate makes them internationally unique – no where else in the world are conferment ceremonies held for masters.

Conferment of master’s degrees is organised at the universities of Helsinki and Jyväskylä, Aalto University and the University of Arts Helsinki. At the University of Helsinki, three faculties – Philosophy, Social Sciences, and Agriculture and Forestry – each hold their own conferment ceremonies for masters (the Faculty of Philosophy is formed of the faculties of Arts, Science, Pharmacy, Biological and Environmental Sciences, and Educational Sciences). The other faculties of the University only organise conferment ceremonies for doctors. At Aalto University, the Schools of Engineering organise shared conferment ceremonies, whilst the School of Business and the School of Arts, Design and Architecture both organise their own. At the University of Jyväskylä, the faculties organise shared ceremonies, and the Academies of the University of Arts Helsinki organised their very first shared ceremony in spring 2018.

Anyone graduating before the conferment from the faculty organising the ceremony may take part and they are collectively referred to as the promovendi. One of the master’s promovendi will be selected as the prima or primus, and another as the ultima or ultimus, based on their thesis grades. Similar nominations will also be made amongst the doctoral promovendi. The master’s promovendi, in particular, will usually be largely responsible for organising their own ceremony. For example, at the University of Helsinki, a Conferment Committee (or Promovendi Committee) consisting of volunteer master’s promovendi will be in charge of organising the conferment ceremony down to the smallest detail, almost without any help from the faculty. The committee chair is known as the gratista.

In addition to the new graduates’ master’s degrees and doctorates, jubilee master’s degrees and doctorates, as well as honorary doctorates, are also awarded at the ceremony. These jubilee masters and doctors took part in a conferment ceremony 50 years earlier and can now take a walk down memory lane as jubilee promovendi. The honorary doctors, on the other hand, are distinguished individuals who have been invited by the university or a faculty to grant them an honorary doctorate.

In addition to the promovendi, many other guests will attend a conferment ceremony, including representatives from the university and faculty in question, but also the companions of the promovendi. A companion of a master promovendus is called a wreath-weaver, as they are charged with making the master promovendus’s wreath from laurel leaves. The companions of the doctor promovendi are called sword-whetters. An official wreath-weaver is also selected for every conferment, who is in charge of making the wreaths of all promovendi attending without companions. Originally, the official wreath-weaver would weave the wreaths of all master promovendi, but as the number of graduates has grown, the title has become increasingly ceremonial.

The Conferrer, the Master of Ceremonies and the Head Marshal, collectively referred to as the officiants, are the main figures representing the university in the organisation of conferment ceremonies. The Conferrer confers or bestows the academic status of master or doctor on the promovendi, the Master of Ceremonies directs the ceremony and the Head Marshal coordinates the heralds. The university’s caretakers are also of a special importance for the conferment ceremony, as they are partly responsible for the ceremony’s arrangements and take part in the processions as bedels.

Furthermore, the student heralds possess a significant amount of knowledge about the conferment tradition. The heralds are representatives of student nations or other student associations who function as decorative elements and assistants at the conferment events, for example by providing instructions to the guests. After graduation, many heralds end up on the Conferment Committee to organise their own ceremony. In general, many people involved in the conferment tradition will take on various roles in arranging several conferment ceremonies.

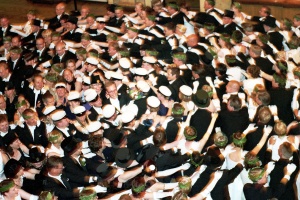

A total of over 1,000 people take part in the largest of the conferment ceremonies, that of the University of Helsinki’s Faculty of Philosophy.

Practising of the tradition

The conferment of master’s degrees is organised once every two to ten years, depending on the university and faculty. It will always entail ceremonies that extend over several days, including a vast number of carefully considered details and symbols, many of which highlight learnedness and education. The following section will focus on describing the conferment ceremony of the University of Helsinki. The traditions at other universities are largely similar, but differ in certain aspects.

The masters’ conferment celebration begins on 13 May with the selection of the official wreath-weaver, which takes place at the master promovendi’s meeting, held in Latin. The official wreath-weaver must be an offspring of one of the university’s professors or some other notable person, and with their choice the promovendi wish to honour said person. The decision is followed by the official wreath-weaver’s proposal, and once they have agreed to this task, the attendants proceed to the Kumtähden kenttä park to the student spring celebration to honour the premier of the Finnish national anthem Maamme. A festive lunch with speeches will conclude these celebrations.

The actual conferment ceremony will last for three days and is held as May turns to June. The dress code is very strict, and a dress coat or an evening dress is required for most of the events. On the first day, which is a Thursday, preparations are made for the conferment by tying the master promovendi’s laurel wreaths and symbolically sharpening the doctors’ swords. The evening ends in a wreath-weaving and sword-whetting banquet, which includes several speeches given mainly in Finnish and Swedish. The multilingual speeches may be about the speaker’s scientific field, or some social topic, and these are an integral part of the conferment tradition.

On the second day, i.e. Friday, the main event, the conferment ceremony, is held in the university’s Great Hall. The ceremony follows a precise choreography and resembles a rehearsed performance in which the promovendi are conferred the rank of master or doctor and granted the symbols of their respective degrees. First the promovendi, then their companions and the university’s representatives enter the hall in carefully arranged processions. After the Conferrer’s speech, the prima or primus master and doctor are presented with a question related to their field of study, and they must answer these. Once the answers have been approved, the conferment may begin. One by one, the promovendi step up, in accordance with a precise choreography, onto the parnasso to receive their academic insignia: the Conferrer will place the laurel wreaths on the heads of the masters and put the golden rings in their fingers, and hand the doctors their swords and hats. Finnish classical music is usually played during the ceremony, and music in general plays an important role in the proceedings. Traditionally, the programme will include at least the Academic March (Promootiomarssi) and Andante Festivo by Jean Sibelius. Often, new pieces are also commissioned for conferment ceremonies (typically cantatas), receiving their premieres at these ceremonies.

The conferment ceremony ends with the ultima or ultimus master’s speech to Finland, after which the participants move in a procession from the Great Hall to Helsinki Cathedral for a conferment service. Alternatively, they may attend a non-denominational event at another location. Processions are a traditional part of academic celebrations, and usually a number of people will gather in Senate Square to watch them. The conferment dinner is held on Friday evening, and its programme includes special conferment poems (often one in Finnish and one in Swedish) or some other form of artistic entertainment commissioned for this event. There will also be more speeches, the most significant one being the speech for the university to which the Rector will reply.

The third day, Saturday, begins with a short trip, typically a sailing trip to a nearby island or around the sea area off Helsinki. This trip is the most informal event during the conferment, and includes a lunch. The day and the entire conferment ends with a ball at the Old Student House, where the participants dance traditional academic festive dances, including a carefully rehearsed masters’ contredanse. The ball also entails several other traditional elements, such as honouring the people key to the conferment by carrying them on a litter. After the dance, the attendants arrange themselves into a nocturnal procession that travels along the streets and across the parks of the city. Along the way, they will stop by statues to give speeches and sing traditional student songs. At sunrise, the procession will make its final stop at the Senaatintori square or the Tähtitorninmäki hill, depending on the faculty, for a speech to the rising sun.

The background and history of the tradition

The masters’ conferment ceremony has remained part of the academic tradition for centuries, with alterations and adjustments made according to each period. The ceremony originates from the Middle Ages: conferment ceremonies were being held in Bologna and Paris as early as in the 13th century. Finland’s conferment tradition is old and dates back to 1643, to the first conferment ceremony of the Faculty of Philosophy, only three years after the Royal Academy of Turku was founded. Since then, the tradition has continued almost unbroken and also spread to other faculties and universities in Finland. The conferment ceremony of the University of Helsinki’s Faculty of Philosophy is still the biggest of Finland’s conferment ceremonies, and nowadays it is held approximately every three years – in 2017 it was held for the 97th time.

The conferment ceremonies of the Faculty of Philosophy in the Royal Academy of Turku remained nearly unchanged as one-day events intended for masters only until the early 19th century. The ceremony began with a gathering at the Conferrer’s home, from where the promovendi travelled in a procession to the Old Academy Building, where the Conferrer would grant them their academic titles. Many of the modern elements of the ceremony, such as the processions and the question posed to the primus master were part of the older conferment ceremonies, as well. The symbols related to the conferment have also remained the same for several centuries: as early as the 18th century, the laurel wreath represented the masters’ achievements. Similarly, the conferment still begins with the Conferrer’s speech and ends with a speech by the ultimus.

The conferment tradition began to change in the 19th century. Examples of new elements included the conferment of jubilee masters and doctors during the same ceremony. In the 1850s, the Finnish national anthem became a fixed part of the conferment ceremony programme. More events were added to the celebration, and the ball, for example, became part of the tradition. In the 1880s, the (Old) Student House became the traditional venue for the ball. All the while, the conferment ceremonies grew in size and developed into noteworthy society events: the history of the tradition is well-known, because the press was eager to write about the related events.

Gradually, the tradition of including masters in the conferment ceremony disappeared from the rest of the world, and the ceremony began adopting features that are only found in Finland. One of these uniquely Finnish features is the appointment of the official wreath-weaver (originally always female). On the other hand, at the end of the 19th century, the tensions with Russia were threatening the continuation of the conferment ceremonies, as they exhibited a spirit of Finnish nationalism. In fact, organising a conferment ceremony required a permit from the Emperor.

Since Finland gained its independence, the tradition has continued without interruptions. The first conferment of the independence era was held in 1919. After World War II, there was a 14 year gap in the tradition; the previous break of such a length had been in the 18th century due to the Great Northern War. Organising a conferment after such a long break was challenging, as the organisers struggled to remember many of the tradition’s details. Therefore, a new tradition of compiling a commemorative book for each ceremony was created. In the 1970s, the conferment ceremonies were considered old-fashioned and elitist, which is why they were kept smaller in scale. However, in the 1980s, the social atmosphere changed and conferment ceremonies regained their popularity.

Over the centuries, academics have felt that celebrating the achievements of graduated masters and doctors in a grand fashion is part of the academic life. Therefore, the conferment tradition has been considered a valuable element of Finnish academia and has maintained its vitality, even through the more challenging times. All the while, the tradition has also evolved, as every conferment and conferment committee has tried to add something new to the centuries-long tradition.

The transmission of the tradition

The conferment of master’s degree is a form of cultural heritage that is created, practised and maintained mainly by young adults. Every ceremony is organised by a new conferment committee, convened by the gratista of the previous ceremony 1–2 years before the next one. In a way, this makes each new conferment ceremony its own independent and separate project, and all recently graduated promovendi and those graduating before the ceremony may participate in organising the ceremony. This means that on the one hand, the tradition is characterised by the voluntary nature of its organisers, and on the other by a centuries-long tradition being combined with the constant change of organisers, which may set certain challenges for the tradition to be passed on successfully.

However, there are several ways in which the conferment tradition is conveyed onwards. First of all, each conferment ceremony is carefully documented: a commemorative book and a register are usually created, in addition to which there is a photographer and a video recording is made of the conferment ceremony. Secondly, the organisers of previous conferment ceremonies pass on the tradition both orally and in writing: for example, the University of Helsinki’s Faculty of Philosophy has compiled a guide dozens of pages long, Lex Promotio, on how to organise the ceremony, and the key people in every conferment committee will update it and pass it on to the next committee’s members. The organisers of previous conferment ceremonies typically consider the tradition important and are happy to provide guidance to new committees in various ways.

In spite of the fact that each conferment ceremony has its own committee, the organisation participants almost always include people who have taken part in previous ceremonies in some capacity. Many conferment committee members have been part of a previous ceremony, for example as heralds, and often those who have participated as master promovendi wish to return to the committee as doctoral promovendi, as well. The officiants and other employees of the university or faculty are also involved in organising the ceremonies and often include experienced conferment ceremony veterans. The University of Helsinki has a special employee mainly in charge of the university-related traditions who offers assistance with the conferment ceremony arrangements. The alumni group Promootion ystävät (‘Friends of Conferment’), operating within the University of Helsinki’s Alumni Association, is glad to help with the conferment ceremony arrangements and passing on the tradition in other ways, as well.

Previous official wreath-weavers are also invited to the ceremony and will take part in the weaving decades after their own conferment ceremony, thus being partly responsible for passing on the wreath-weaving tradition. When it comes to the heralds, the tradition is passed on by the student nations and other associations appointing heralds. The jubilee promovendi are also part of passing on the tradition, including the idea that every new ceremony is a jubilee ceremony for the one held 50 years earlier. It is common practice to borrow one of the details from the ceremony held 50 years prior to the current ceremony, which both renews the tradition and conveys it on to the future generation.

Every university and faculty has its own versions and variants of the conferment tradition, but often practices that have proven successful will be utilised at several locations. In particular when it comes to the conferment of doctor’s degrees, the conferment tradition has spread in varying forms to nearly all Finnish universities. Therefore, it would be desirable for the masters’ conferment ceremonies to be more widely adopted, as well.

The future of the tradition

Currently, the conferment tradition remains strong. In recent years, there has been an abundance of volunteer organisers, and during the past decade the ceremonies have also broken records in their attendant numbers. Based on the current situation, the future of the conferment tradition looks bright and safe, although it is possible that at some point, similarly to the 1970s, society will begin to think that the ceremonies are old-fashioned, elitist and unsuitable for modern day society.

Recent developments in the academic world can be considered the main threat to the conferment tradition, with the reductions to universities’ budgets and forceful attempts to restrict study times. Universities have viewed the conferment ceremonies as an important part of academic life and supported them both financially and by providing their facilities to be used as the venues. However, as the universities’ budgets tighten, the funding for the ceremonies may also face problems and the possible increase in the attendance fees resulting from this could lower the number of participants.

The shortening of study times and attempts at getting students to graduate faster, on the other hand, pose challenges in terms of active student participation and various student traditions that have a strong connection to the conferment ceremony. Many of the phenomena present at these ceremonies originate from a strong student tradition, with which the organisers of the ceremonies become familiar during their studies, for example at the annual balls held by student nations and other student associations. If the students’ ability to participate in the activities of these associations deteriorates, the future conferment ceremony organisers will not have the necessary overall knowledge regarding academic traditions.

However, the conferment tradition has managed to stay alive in Finland for nearly 375 years, through war, famine and political turmoil. Therefore, the tradition can be considered able to retain its vitality and continue on even in challenging conditions. Another factor guaranteeing the continuation and vitality of the tradition is the fact that conferment ceremonies adapt to their time. Newer examples of this include the elements added in the 21st century: male official wreath-weavers and the non-denominational gatherings as an alternative to the conferment service.

The community/communities behind this submission

Helsingin yliopiston alumniyhdistys

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Promootio akateemisena juhlana. Toim. Johanna Ilmakunnas. SKS 2010. ISBN 978-952-222-274-9

Klinge et al.: Helsingin yliopisto 1640-1990. Otava 1987.

Promootio vuodelta 1961 Artikkeli

Websites

Helsingin yliopiston valtiotieteellisen tiedekunnan promootio 2016