Finncattle and tradition of cattle husbandry

| Finncattle and tradition of cattle husbandry |

|---|

| In the national inventory |

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

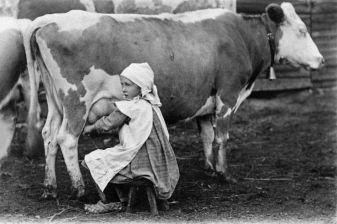

The shared journey of humans and cattle in Finland is estimated to have begun at least around 4000 years ago. This marked the beginning of a period when cattle became an integral part of people's subsistence farming. Cattle farming skills were passed down from one generation to another, with knowledge being transferred from mothers to daughters or from the experienced housewives to their daughters-in-law. However, the accumulation of traditional knowledge and skills began to decline with the modernization of agriculture following the second world war, leading to the abandonment of the Finnish native cattle breed. The number of experts in Finncattle has dramatically decreased, and traditional knowledge is at risk of disappearing altogether unless special attention is paid to it now.

Biodiversity loss has increased general interest in the Finnish native cattle breed. As an indigenous breed, it remains genetically diverse and is therefore suitable for various purposes. Among these purposes, the grazing of traditional biotopes contributes to biodiversity conservation. With the growing interest, there is a renewed need for cattle husbandry skills, especially since novice cattle keepers lack the essential knowledge that has been passed down through generations.

Finncattle breeders effectively utilize social media networks. Online groups bring together people of different ages and professions who share an interest in Finncattle, whether as a hobby or profession. These groups have thousands of members, even though the actual number of Finncattle breeders is now counted in the tens. Breeders can be categorized as conventional milk producers, self-sufficient producers, and increasingly, as grazers of Finncattle, producers of beef, and maintainers of biodiversity.

In 2021, Finncattle breeders established an association whose main mission is to support the use, breeding, and preservation of diverse genetic heritage of native breeds. Additionally, the association provides peer support to its members and acts as an advocate for their interests. Currently, Suomenkarja ry (Finnish Cattle Association) has about 60 members.

Practising of the tradition

"Finncattle" is a collective term for the Eastern, Western, and Northern Finncattle, three native cattle breeds. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) criteria, all Finncattle breeds are classified as endangered.

Eastern and Northern Finncattle are classified as multipurpose breeds based on their intended use. They are suitable for both milk production and, as excellent grazers, for landscape management and meat production. Finncattle individuals are kept in farms, in animal-assisted activities, and as pets. All Finncattle breeds share relatively small size and polledness, meaning they do not have horns.

Eastern Finncattle are commonly referred to as "kyyttö," although originally it referred to the red-sided and white-striped or white-backed color type of cattle. Eastern Finncattle have found their niche in traditional grazing due to their good maternal characteristics, temperament, and agility. The number of Eastern Finncattle is increasing, and it has become the most common Finncattle breed, with slightly under 2,000 individuals.

Northern Finncattle, also known as Lapland cow (lapinlehmä) , is the rarest of the Finncattle breeds. There are fewer than 900 breeding females . The population of Northern Finncattle is steadily increasing. In contrast, the situation for Western Finncattle is the most concerning, as this formerly most common dairy cattle breed is barely maintaining just over a thousand individuals.

The unique characteristics and genetics of Finncattle have largely evolved in response to the needs of people in the past. In subsistence economies, domestic animals were an integral part of people's daily lives, both in rural areas and cities. Domestic animals hold a strong place in Finnish culture, beliefs, and the environment. They represent our living cultural heritage, protect biological diversity under the Finland’s national genetic resource program for agriculture, forestry and fisheries , and contribute to global biodiversity for food security. The long-established genetic diversity has given Finncattle good prospects for adapting to changing environments in the future.

Key areas of Finncattle husbandry include care (naming, feeding, milking), grazing, cattle calls, and food culture.

Traditional Finncattle husbandry still includes many aspects related to animal care (feeding, grazing culture, milking) and human-animal relationships. The husbandry of Finncattle differs from one of the commercial breeds. Finncattle-related traditions are also found in food traditions and music (cattle calls, work songs, cattle bells).

Examples of Finnish cattle farming traditions:

1. Raising: In general, Finncattle grow more slowly than extensively bred commercial breeds, although the intensity of feeding has a significant impact. According to tradition, Finncattle are said to grow until the 4th calving, which is about 6 years old. Despite their slow growth, Finncattle reach sexual maturity very early, which should be considered in grazing practices.

2. Naming Cows: Finncattle are treated as individuals. Farmers often consider cows as work colleagues, pets, or even family members. Farms that participate in production control name calves born in the same year with the same initial letter. For example, calves born in 2023 will be named with the letter "V". Small-scale farmers often use nature-related names for their calves. Naming may follow a pattern where the cow's lineage is recognizable. Traditional naming often used the suffix "kki" in the west (e.g., Lemmikki and Mansikki) and "ke" in the east (Lemmike and Mansike).

3. Milking: Finncattle adapt to both modern robotic barns and hand milking for small-scale production. Due to their lower milk production, Eastern Finncattle are better suited for small-scale production, as suckler cows , and for landscape management. However, the expected average production of Eastern Finncattle is about 4,500 kilograms of milk per year. In contrast, Ahlman's Western Finnicattle, a live gene bank population, had an average production of over 8,000 kilograms in 2019. Northern Finnicattle's production level falls between Eastern and Western Finncattle. Old milking routines involved many traditions, most of which have disappeared, such as "ripsiminen" or "ripsuminen" and "lehmisavut." During milking, branches of alder or birch were used to chase away flies, mosquitoes, and horseflies from the cow's back to keep them calm. "Ripsiminen" was also used to train heifers for milking. Usually, children were responsible for "ripsiminen." In some parts of Finland, it was called "ripsuminen." In some regions, "hosa," made from alder branches, was used. The previous day's "hosa" was burned in cow sheds.

4. Field Traditions: In spring, idle animals that did not require daily care, such as bulls, heifers, and calves, were often taken far away from the main farm. Summer grazing was even practiced on island pastures, to which the cattle were transported either by ferry or by swimming. In autumn, the cattle were brought back home to the barn. This tradition is still alive.

5. Summer Barns: In the northern Tornionjokilaakso region, summer barns were used where cattle were kept during the summer. The riverside villages were dense, and there were no grazing lands within the homestead, so cattle were taken to remote areas for grazing. In the past, women, elderly women, field maids, or young girls accompanied the cattle to the backwoods for the summer. As part of the tradition, the winter barn was maintained during the summer; it was cleaned and even lived in. In modern times, wooden-frame buildings have been used as summer barns, and their use has increased, especially in landscape management, where cattle need to be moved far distances for summer grazing.

6. Grazing and Traditional Biotopes: Finncattle, with their relatively small size, are agile grazers and can thrive on modest nutrition by turning natural grasses and shrubs into meat and milk. They can also graze in waterside pastures, as Finncattle are known to graze in the water. Their polled nature makes them suitable for dense terrain, as they don't harm the trees. Finnish traditional biotopes (meadows, pastures, cleared forests, and forest pastures) have evolved over hundreds, even thousands, of years due to traditional cattle farming. When grazing ceases, the species diversity of traditional biotopes diminishes and eventually disappears as they become overgrown. Grazing is also beneficial for combating climate change since carbon sequestration continues for an extended period in grazed areas. Fallen trees that sequester carbon can also be found in these areas.

7. Cattle Calls: The tradition of cattle calling is still alive among some Finnish cattle breeders. In the past, each tribe had its own way of calling cattle, so there are known regional variations such as Karelian, Häme, Åland, Ostrobothnian, and Savonian versions. Besides regions or tribes, there were also house, family, and village-specific differences in cattle calls. Calls often included a wide range of stylistic features. Musically rich and ornamented calls are among the oldest and most developed forms of work music in Northern Europe. It is also known that singing or work songs were used in human-animal interactions.

The background and history of the tradition

The History of Humans and Cattle in Finland

Prehistory: Cattle have been raised in Finland for thousands of years, adapting to the prevailing conditions, including enduring cold, long, dark winters and utilisinglocal vegetation. This resilient and adaptable cattle population continued to exist from prehistoric times through the Middle Ages to the present day. The descendants of Finland's prehistoric cattle still live among us as Finncattle, carrying the genetic heritage shaped by past cattle farming practices.

Early Modern Period and Traditional Agriculture: The development of cattle farming gained momentum when the purpose of keeping cattle did not solely require them for slaughter. One of the primary reasons for raising cattle in those times was to provide manure for fields. Later on, butter became a valuable commodity used for paying taxes. It's worth noting that before the mid-1800s, almost all cattle in Finland were mainly native landrace cattle; imported animals were mostly found on large estates. It was only in the latter half of the 19th century, during a period of interest in crossbreeding various livestock, that foreign and crossbred animals significantly increased in numbers. The official establishment of Finncattle dates back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries when breed associations were founded for all three Finncattle breeds, maintaining the pedigree registers required for purebred breeding. However, during this period, as the focus shifted towards dairy farming, foreign breeds such as Ayrshire gained attention.

World War II: World War II and the subsequent strong development of dairy farming especially affected Eastern and Northern Finnish cattle. Karelian evacuees were only able to save a portion of Eastern Finncattle as they resettled across Finland. During the Lapland War, Sweden participated in a rescue operation for the Northern Finncattle population. Both evacuations resulted in significant losses in cattle numbers. For instance, the bulls of Northern Finncattle never returned from their evacuation journey, and the number of returning cows was smaller than the group that left. The post-war period also marked the end of the golden age for Finncattle breeds, as the breed associations were merged when foreign breeds replaced Finnish cattle.

Modernization of Agriculture: In the late 1970s, it was realized that Eastern and Northern Finncattle were on the brink of extinction. The numbers of both breeds had dwindled to mere tens; there were only about twenty Northern Finncattle left. The plight of Northern Finncattle was exacerbated by the lack of artificial insemination bulls. The existence of a few determined livestock keepers and last-minute efforts by enlightened authorities saved Eastern and Northern Finncattle from ultimate extinction. Measures to save these breeds were initiated by the government on school farms in the 1970s. A decade later, the Finncattle gene bank herds were placed on three prison farms: Pelso, Sukeva, and Konnunsuo.

Present Day: The continuation of Finncattle-related traditions naturally depends on the preservation of Finncattle as a living breed. Although Finncattle breeds are now protected and subject to official genetic resource program measures, some, such as Western Finncattle, have alarmingly declined in recent years. The goal of the national genetic resource conservation program is to sustain both Finncattle as a breed and the associated cultural heritage in a sustainable manner. Sustainable solutions involve considering environmental, current, and future generation needs, as well as economic aspects.

In August 2022, the last gene bank in Pelso closed its doors. The living gene banks of Finncattle continue to operate on school farms: the Western Finncattle gene bank is in Tampere at AhlmanEdu’s school farm, the Eastern Finncattle in Kajaani at the Kainuu Vocational College's natural resources education farm in Seppälä, and the Northern Finnish cattle in Rovaniemi at the Lappia Vocational College's Loue campus. These school farms play a pivotal role in preserving and passing on the traditions of Finnish cattle farming to new generations.

The transmission of the tradition

Previously, cattle husbandry was primarily the responsibility of women, and the knowledge related to the care of Finncattle was passed down from one generation to the next, from mother to daughter, or from the experienced farmwife to her daughter-in-law. Later-established official organizations, such as breed and breeding associations, played an important role in transferring this knowledge. Throughout challenging times, Finland has had individuals who have continued the Finncattle farming tradition through their own efforts. Nowadays, Finncattle breeders also operate as entrepreneurs, offering activities such as farm tourism or other animal-assisted activities. You can get to know the Finncattle farming tradition by visiting farms, cow camps, or shepherd vacations.

The living gene bank herds in Alhman, Loue, and Seppälä pass on knowledge related to animal care and handling to their students. In addition, Finland's National Gene Resource Program for Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, in collaboration with the Nordic Gene Resource Center (NordGen) and the Faba Cooperative that provides breeding and advisory services for cattle breeds, helps maintain the genetic resources of Finncattle.

In 2021, Finnicattle breeders established an association with the primary mission of supporting the use, breeding, and preservation of diverse genetic heritage of native breeds. Additionally, the association offers peer support and acts as an advocate for its members. The association currently has about 60 members.

Social media platforms have become an important peer support network for Finnish cattle breeders. There are groups such as Suomenkarja - Aito Suomalainen Selviytyjä; itäsuomenkarja eli kyyttö; pohjoissuomenkarja; Suomenkarja lypsylehmänä, as well as various groups maintained by different projects.

Safeguarding tradition

The profitability crisis in agriculture has created new threats to the future of Finncattle, especially in dairy farms. The preservation of the unique cattle husbandry heritage associated with Finncattle depends on whether Finncattle can be saved from extinction. Maintaining entire animal populations is a challenge unless new sustainable utilization solutions, suitable for the modern era, are found for their existence. The age-old traditional grazing use of Finncattle has become a crucial factor in the revival of Eastern Finncattle from the low point of the 1970s and 1980s to a population of nearly two thousand thriving individuals.

How is tradition recorded?

Because cattle have been an integral part of human life for centuries, related traditions have been consciously and, above all, indirectly recorded through various archival sources. The quantitative development of Finncattle has been documented in tax and statistical sources since at least the 1500s. Information related to cattle care, feeding, and breeding has been recorded in various agricultural administration archives and other official documents, as well as in the archives of individual farms and agricultural schools. In addition, collection calls related to cattle and associated memories have been organized in various heritage collections, the results of which can be found in both archival and museum collections. Cattle-related information has also been documented in community historical accounts created on a hobbyist basis. In addition to diverse written materials, photographs related to cattle and cattle husbandry traditions have been preserved in the collections of many archives and museums (see Finna). The material heritage related to this topic can be explored in various national and local museums. The fragmentation of tradition preservation across multiple entities and the extent of the subject itself demonstrate the extensive connection of tradition to the lives of people in the past.

The continuation of cattle husbandry tradition still relies on the tacit knowledge of individual cattle keepers, and much of this traditional knowledge remains fragmented and uncollected.

The future of the tradition

Finncattle, with their traditions in cattle husbandry , are part of our cultural heritage and are protected by the Finland’s National Genetic Resources Programme of Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, contributing to Finnish biological diversity and global biodiversity as recognized by the FAO to ensure food security. The genetic diversity that has developed over a long period ensures the potential of native breeds to adapt to changing environments in the future.

Finland, like many other countries, is committed to preserving biological diversity, which includes agricultural genetic resources with native breeds. The preservation of the unique cattle husbandry tradition associated with Finncattle depends on whether Finncattle can be saved from extinction.

In 2023, Finland faces a situation where we are at risk of losing a classified native animal breed. One of the recently most endangered native animal populations is the Western Finncattle, one of the three native cattle breeds in Finland. In the general discussion, there has been insufficient awareness of the critical situation regarding the future of an entire animal breed. With the extinction of Western Finncattle, we would also lose the genetic diversity and cultural heritage that has been intertwined with it in Finland for thousands of years.

Today, significant changes in the role, appreciation, and economic importance of animals put the future of native breeds in jeopardy. The ancient use of Finncattle as traditional grazers has emerged as a crucial factor in the recovery of Eastern Finncattle from the low point of the 1970s and 1980s, when their population dwindled to nearly two thousand individuals. Now, it is crucial to find a positive turnaround in the current trend towards extinction for all Finnish cattle breeds, especially the Western Finncattle.

The community/communities behind this submission

Kotieläinsektorin johtaja, FT Mervi Honkatukia

Osteologi, dosentti, FT Auli Bläuer

Historian tutkija, FT Hilja Solala

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Bibliography

Bläuer, Auli 2015: Voita, villaa ja vetoeläimiä. Karjan ja karjanhoidon varhainen historia Suomessa. Karhunhammas 17. Arkeologia, Turun yliopisto, Turku.

Halmemies Taina. 2019. Kutsu Karjasi Koolle: Karjaperinteestä. JAMK

Honkatukia, M. 2021. Itäsuomenkarjan tilanne vakaa, länsisuomenkarjan huolestuttavasti harvinaistumassa. Elonkierto.

Jumpponen, M. 2019. Suomenkarjan ruokinnan haasteet.

Kaltio, M. J. 1958: 60 vuotta suomenkarjan jalostusta. Suomen karjanjalostusyhdistys r.y.

Karja, Miia & Lilja, Taina (toim.) 2007: Alkuperäisrotujen säilyttämisen taloudelliset, sosiaaliset ja kulttuuriset lähtökohdat. Maa- ja eläintarviketalous 106. Maa- ja elintarviketalouden tutkimuskeskus, Jokioinen.

Kroløkke C, Nørkjær Bang A, Ovaska U, M Honkatukia. 2023. A flock of one's own: Nordic human-mountain cattle kinship-making practices. Society & Animals, 1-25. ISSN1063-1119 (in press).

Maijala, Kalle 1998: Jalostustyöllä tulosta. 100 vuotta naudan- ja sianjalostusta. Suomen Kotieläinjalostusosuuskunta.

Solala, Hilja & Honkatukia, Mervi (toim.) 2022: Snöhvit, Punakorva, Fjellblom. Pohjoisten tunturikarjojen historia, nykypäivä ja tulevaisuus. Näyttelyjulkaisu samannimisestä museonäyttelystä. 3MC – Pohjoiset tunturikarjat. Kulttuuriperintö ja geenivarat -hanke 2022.

Toivio (nyk. Solala), Hilja 2014: ’Risteytyksistä maatiaisrotuihin. Professori Victor Prosch ja kotieläinjalostuksen murros 1800-luvun jälkipuolella’. Teoksessa Eläimet, Lähde – Historiatieteellinen aikakauskirja 2014. 96–122.

Online sources

NordGen, Alkuperäisrodut

Paja Ahlaman "Syvennä tietoasi suomenkarjasta!"

Maa- ja metsätalousministeriö, "Suomen maa-, metsäja kalatalouden kansallinen geenivaraohjelma"

Ympäristöhallinnon yhteinen verkkopalvelu "Perinnebiotoopit"