Glassmaking Tradition

| Glassmaking Tradition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

Glassmaking based on glassblowing is more than 2000 years old. In the past glassmaking has employed thousands of workers in Finland, today glass industry has almost disappeared. At the moment the only industrial glass producer is Iittala glassworks. Iittala employs about 200 people of which 25 percent are glassblowers. In Finland there are also several smaller ‘hotshops’ that are either small businesses or cooperatives, that make blown glass.

Tavastia Vocational College educates glassblowers (Vocational Qualification in Crafts and Design) in Nuutajärvi, Sastamala Education Consortium in Ikaalinen. This education gives basic competence to gain employment in the glass branch. Annually about 10 glassblowers graduate, most of them continue their education in some cultural field, some of them will continue to work with glass. Since 1993 those that remained in the glass business have created a new strong tradition of glassmaking, this hardy group has succeeded in promoting non-industrial glassmaking.

The Finnish Glass Museum actively collects information relating to the latest developments in glassblowing in Finland. Every five years the Finnish Glass Museum arranges an exhibition called Finnish glass lives, which demonstrates the huge changes in the Finnish glass industry. The Finnish Glass Museum with its exhibitions and research work helps preserve glass traditions and encourages new ideas.

Practising of the tradition

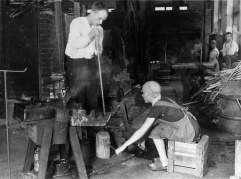

Glassblowing is the basic method of glass manufacture. Glass can be free blown, but mould blowing, either fixed or turned, is more common. The glassblower of course does more than just blow glass. The glassblower traditionally had assistants and the glass objects were not made by him alone but were made by a team called a ‘chair’. Nowadays some glassblowers work alone with the help of tools that they have developed. Some glassblowers cooperate with professional designers and artists to make one-off works of art, prototypes and even serial production. Some glassblowers have a background in art or design which helps them create their own works.

The problems in the glass industry both internationally and in Finland have led to different solutions. In Finland since the 1990’s more glassblowers have been trained than ever before. Many of the most respected glassblowers have also been teachers. The original plan was to train glassblowers for the needs of the glass industry, however most of these glassblowers have been forced into self-employment. Many new glass studios have been founded near the old glassworks in an attempt to preserve glass traditions. In Nuutajärvi and Riihimäki these hotshops have almost become leisure centres for retired glassblowers! Here traditions are passed down, though not as effectively as in the old glassworks. Nowadays many young glassblowers go abroad to get work experience in foreign glassworks, from these experiences and with the help of old glassblowers a firm base on to which to build professional abilities can be formed.

The background and history of the tradition

Glassblowing was invented in the Middle East over 2000 years ago, blown glass arrived in Finland already in the Iron age. When the first glassworks was founded in in Finland in 1681 glassblowing was almost the only form of glass manufacture. The first glassblowers came to Finland from Sweden but they were originally German. In the glassworks the glassblowers role was central during the 19th century and even later in Finland. The owners of the glassworks often knew nothing about glass making. Industrialization brought technical experts into the industry. The ‘chair’ or work team grew in size up to 10 persons, assistants did the lower skilled work for which they were paid less.

The skills of the glassblower have been appreciated in later times as well. Sometimes there has been a conflict of identity - on the one hand he was a skilled artisan and on the other an industrial worker. The ‘chair’ foreman was a highly respected professional, a master glassblower, and apprentices also wanted to work under the best foreman.

The transmission of the tradition

Today the glasswork traditions are upheld by schools but also with the active help of old master craftsmen and the local community. Students have to have practice in hotshops or artists studios. In Nuutajärvi there have been held many workshops in which special techniques have been taught by either Finnish or foreign glassblowers. Knowledge is also gained from retired glassblowers, many of whom visit the small hotshops on a daily basis.

Tavastia Vocational College provides the possibility for glassblowers to gain extra qualifications. In September 2014 the Finnish National Board of Education degreed on national qualification requirements for further vocational qualification (journeyman) and specialist vocational qualification (master) in glassblowing. Häme University of Applied Sciences arranges glassblowing sessions for their design students to promote cooperation with the glassblowers.

Glassblowing differs from many other handcrafts in one respect, it is nearly impossible to practice as a hobby due to high costs.

The future of the tradition

The knowledge, craft and skills of handmade glass production was inscibed on the UNESCO’s Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in December 2023. The inscription of a multinational nomination is a tribute to glassblowing and design based on intangible cultural heritage. The multinational nomination was joined by France, Finland, Germany, Spain, the Czech Republic and Hungary. In Finland, the nomination process was supported by 17 actors in the field of glass. The Finnish Glass Museum coordinated the application in collaboration with the Finnish Heritage Agency. The collaboration in the nomination process has strengthened the networks in the glass field both internationally and in Finland.

The survival of the glassblowing tradition relies on the continuation of education and the support of glassblowing and design businesses. This support does not have to be state or local financial funding, but rather improving the value and appreciation of handcrafts as part of our cultural heritage.

Hotshops organise workshops and courses where the teachers are senior glassblowers or foreign experts. Cultural and experience tourism brings visitors to the glass studios, thus increasing the knowledge and appreciation of handcrafts with the public. The Finnish Glass Museum promotes tourism in cooperation with the glass businesses.

The community/communities behind this submission

The Finnish Glass Museum, Suomen lasimuseon ystävät ry (Friends of the Finnish Glass Museum), Nuutajärven lasikylän kulttuurisäätiö, Riihimäen Lasinpuhaltajakerho ry, Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture HAMK University of Applied Sciences, Tavastia vocational college, Sastamala Educational Consortium

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Glass studios and hotshops

Bianco Blu, Hytti ry, Lasismi, Mafka, Nuutajärvi, Lasistudio Pekka Paunila, Soda Shop Design, Lasistudio Jan Torstensson,

Websites

UNESCO's website on the knowledge, craft and skills of handmade glass production

Riihimäen Lasinpuhaltajakero ry materials for primary school students

Litterature

Reijo Ahtokari, Suomen lasiteollisuus 1681-1981, Helsinki 1981.

Vilho Annala, Suomen lasiteollisuus I / II, Helsinki 1931 / 1948.

Markku Annila, Vanhat lasini : suomalaista lasia 1700-luvulta 1900-luvun alkuun, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 2006.

Kaj Franck, teema ja muunnelmia, theme and variation, Heinolan kaupunginmuseo, Lahti 1987.

Helena Tynell, Design 1943-1998, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 1998.

Humppila, lasitehdas tien varrella, Lasitutkimuksia - Glass Research XIV (2002), Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 2002.

Kaisa Koivisto, Kolme tarinaa lasista, Lasitutkimuksia - Glass Research XIII, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 2001.

Kaisa Koivisto (ed.), Ilmatar - Skymaiden, Glass by Nanny Still, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2003.

Kaisa Koivisto, Markku Salo: Cries and Whispers / Huutoja ja kuiskauksia, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2008.

Kristalli! Suomalaisen kristallin tarina, Lasitutkimuksia - Glass Research XII, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 1999.

Lasin taide, The Art of Glass, Kaj Franck 100 vuotta - 100 years, Kyösti Kakkonen Collection, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2011.

Uta Laurén (ed.), Gunnel Nyman, Beauty Captured in Glass, Lasiin vangittu kauneus, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 2009.

Antti Metsänkylä - Pirkko Suutari, Työryhmä: verstakko, Museovirasto, Helsinki 1992.

Virpi Nurmi, Lasinvalmistajat ja lasinvalmistus Suomessa 1900-luvun alkupuolella, Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistys, Helsinki 1989.

Nuutajärvi - Kartano ja lasipruuki, Museovirasto, Helsinki 1983.

Nuutajärvi, 200 vuotta suomalaista lasia, 200 Years of Finnish Glass, Hackman, Tampere 1993.

Oiva Toikka, Lasi, Glass, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 1988.

Oiva Toikka, Lasia, Nuutajärveltä, Amos Andersonin taidemuseo, Helsinki 1995.

Osakeyhtiö Kumela, lasimaalaamosta tehtaaksi, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 2002.

Mirja Orvola (toim. ed.), Heikki Orvola, Craft Design, Pohjoinen, Oulu 2000.

Riihimäen Lasia, Glass from Riihimäki, Riihimäen Lasi Oy 1910-1990, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2010.

100 vuotta Karhulan lasia, Lasitutkimuksia V, Suomen lasimuseo, Riihimäki 1989.

Marja-Leena Salo, Into & polte - Nuutajärven lasikylän tekijöiden tarinoita, Nuutajärvi 2015.

Suomalaisen lasin juhlaa, Iittala 125, Designmuseo, Helsinki 2006.

Suomen lasi elää, Finnish Glass Lives, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 1986.

Suomen lasi elää 2, Finnish Glass Lives 2, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 1990.

Suomen lasi elää 3, Finnish Glass Lives 3, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 1995.

Suomen lasi elää 4, Finnish Glass Lives 4, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2000.

Suomen lasi elää 5, Finnish Glass Lives 5, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2005.

Suomen lasi elää 6, Finnish Glass Lives 6, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2010.

Suomen lasi elää 7, Finnish Glass Lives 7, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2015.

Tapio Wirkkala, Hand, Eye and Thought, Taideteollisuusmuseo, WSOY, Helsinki 2000.

Tapio Wirkkala, Lasin ja hopean runoilija, A Poet in Glass and Silver, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2013.Timo Sarpaneva, Keuruu 1986.

Timo Sarpaneva, Kokoelma, Collection, Designmuseo, Helsinki 2002.

Timo Sarpaneva, Taidetta lasista, Glass Art, The Finnish Glass Museum, Riihimäki 2015.

Markku Tasala, Lasintekijöiden tarinoita Iittalasta, Designor Oy Ab 2001.