Picking mushrooms

| Picking mushrooms |

|---|

| In the national inventory |

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

Almost 5500 species of fungi growing in Finland depending on the calculation method and at least a couple hundred species are edible. The annual mushroom yield is around 1.5 to 4 billion kilos, of which humans harvest about 2–10 million kilos.

Identifying and using mushrooms are skills that have mostly been passed down the generations as oral tradition, and even today in Finland the majority of Finns received their first lessons regarding mushrooms from their families or relatives.

The Finns are quite avid mushroom pickers. The mushroom picking activity of Finns has been studied by e.g. Natural Resources Institute (formerly Forest Research Institute) and University of Eastern Finland (formerly University of Joensuu).

The National Inventory of Natural Recreation (LVVI) survey has been carried out three times in Finland by 2022. The third and most recent inventory was conducted in 2019-2021, and according to the results, 40% of Finns go mushroom picking annually. In this millennium, the popularity of mushroom picking has remained quite stable, with 38% in the first inventory (in 1998-2000) and 40% in the second inventory (2009-2010). Mushroom picking is especially a hobby of middle-aged and older baby boomers, but mushroom picking carried out by the young people has also increased over the past 20 years.

The University of Eastern Finland has studied the picking of natural mushrooms by Finnish households in 1997-1999 and 2011. In particular, the research has examined quantities collected for own use and sale, pickings per species, and participation in picking (including participation in commercial picking). For example, in the plentiful mushroom year 1998, a total of 16.1 million kilograms of mushrooms were picked (7.3 kg per household). In 2011, the harvest of many species of fungi was also good, and at that time the total picking was 15.0 million kilograms. The 1999 mushroom crop remained small, which was clearly reflected in the quantities picked (1.5 kg/household, 3.3 million kg).

Participation in picking ranged from 23% (in 1999) to 47% (in 1998) — thus significantly higher than in LVVI studies. One key reason for the difference in results is that the University of Eastern Finland study calculated the results for individual years, whereas the results of the LVVI studies are based on data collected over several years, with participation rates reflecting more of the measurement periods average figures. Between 1997 and 1999 and 2011, the majority of mushrooms (85-90%) were picked for household own use. Only a small percentage of households participated in the commercial picking of mushrooms, with the highest percentage of commercial pickers in 1998 (1.3% of households) and the lowest in 1999 (0.3% of households).

In Finland, statistics of trade volumes, kilograms and picking revenues of natural berries and mushrooms have been collected since the late 1970s, with the help on so called Marsi research. In the survey, information is asked of companies engaged in the trade in berries and mushrooms (so-called “organised trade”). Among other things, one can see from Marsi statistics that trade revenue volumes reflect annual crop levels. They also show that natural mushrooms are picked for trade mainly by domestic workforce, unlike natural berries.

The Finnish Mycological Society was established in 1948. The society has two publications: Karstenia, intended for scientific research results in the field of mycology and Sienilehti, a journal intended for hobbyists. In the 1970s, regional mushroom associations were established under the name of the Finnish Mycological Society in order to promote identification of mushrooms and their use for food. In 2017, 16 active regional mushroom associations were operating in Finland.

The central organisation for vocational education started the training of commercial mushroom pickers in 1969. The objective was to increase the utilisation of wild mushrooms – as much of the yield of edible mushrooms is left unpicked – and ensure the safety of mushrooms sold. Today, The Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira maintains a directive list of marketable mushrooms, i.e. recommended edible mushrooms. In 2022, this list featured 22 mushroom species or aggregates.

Today, in addition to mushroom associations, information about edible mushrooms is shared by, for example, museums of natural history, community colleges and adult education centres, the Martha organisation and the Arctic Flavours Association.

Practising of the tradition

For many Finns, picking wild food mushrooms is a major form of recreation, for others it is essential in terms of domestic needs, and for some it is a way of making additional income. Historically, Eastern Finns have been the most active sales pickers: for example, in the period 1990-2021, 84% of the amount of mushrooms entered into organised trade has been collected from the Eastern Finland region. In 2021, Eastern Finland accounted for 94% of the sales volume of mushrooms and this generated tax-free extraction revenue of approximately 2.1 million euros.

Research by the University of Eastern Finland shows that in the late 1990s, milk caps were Finns' favourite mushrooms, as milk caps accounted for up to half of the total picked. Milk caps were also the group of mushrooms picked most for sale. In 2011, milk caps accounted for about a fifth of the total picks, a roughly equal share as chanterelles. Other mushroom species (yellow foot, false morel, black chanterelle) were picked more than in the late 1990s. In 2011, the porcinis made up a tenth of the total pick, but nearly a quarter of the commercial pick.

A study by the University of Eastern Finland showed indications of a “porcini boom” in this millennium. The Marsi statistics clearly show how porcinis have become the number one mushroom for commercial picking. Over the past twenty years, on average, the share of porcinis in the trade volume of natural mushrooms has been higher than that of milk caps. For example, in 2021, 0.8 million kilograms of natural mushrooms entered into the organized trade, of which porcinis accounted for 84%.

Picking edible mushrooms is by far the most popular mushroom-related hobby in Finland. Most often, people go mushroom picking from their own front door or their summer cabin, going to nearby forests. Mushroom picking is easy in Finland, as the public right of access allows everyone to pick wild mushrooms, even on land owned by someone else, as long as they do not go too close to houses or yards. Picking edible mushrooms is usually also allowed in nature reserves, excluding the national parks with strictest protection policies.

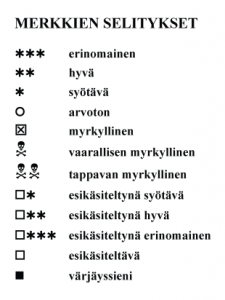

The Finnish mushroom tradition includes usability labels for mushrooms. The first scale used was mostly based on the estimates of Professor Toivo Rautavaara. Since then, these labels have changed many times. The Finnish view on the usability of mushrooms has always been slightly different from that of other countries. For example, many species of lactarius that are considered good, edible mushrooms after boiling them are labelled as poisonous in some European countries. Untreated, false morel is deadly poisonous, but in Sweden eating it is not recommended even after careful boiling.

Edible mushrooms often require pretreatment. Mild-tasting mushrooms are usually just roasted on a dry skillet until excess fluid has been removed. The tart russulas, most lactarius species and, for example, Armillaria borealis and shaggy parasol mushrooms need to be boiled for 5 to 10 minutes, depending on their level of tartness. Gyromitra esculenta growing in spring are deadly poisonous when fresh, so they need to be parboiled twice, for five minutes at a time. The water must be changed in between. The mushroom’s poison dissolves in water, so the kitchen must be kept well ventilated during the boiling process.

Mushrooms can be preserved in many ways. Preserving lactarius species by salting them is one of the most popular, traditional preservation methods. Mushrooms with thin fleshy inner parts (trama), such as black chanterelle and funnel chanterelle, are easiest to preserve by drying them. Drying is also a great way of preserving russulas and boletaceae, cut into thin slices. Vitamins and trace elements are well preserved in dried mushrooms and their flavour becomes stronger. This way, mushrooms can also be preserved for several years. Chanterelles, albatrellus ovinus and hydnum repandum (hedgehog mushroom) can be preserved by freezing them in their own liquid. Mushrooms can also be preserved in various marinades.

At the beginning of the last century, mushrooms were usually served as a side dish to potatoes. They were made into a milk-based stew or fried with onion and fatty pork. Salted mushrooms mixed with cream and onions as well as various mushroom stews are still popular side dishes to potatoes.

Mushrooms have also been used in soups. In the past, ‘ripakeitto’ was a traditional Karelian dish; a soup with dried leccinum species mushrooms, potatoes, onion and barley groats. Patties and balls made of minced mushrooms are also part of the old mushroom dish tradition. Mushroom fillets rolled in egg and flour were made of mushrooms with thick, fleshy parts, such as albatrellus ovinus and boletaceae.

Picking edible mushrooms is not the only mushroom hobby. Mushrooms can also be used for dyeing, for example. Certain mushroom species are excellent for dyeing various natural materials, such as wool yarn. The blood red redcap yields the strongest red and orange hues.

Some mushroom hobbyists specialise in the continuous development of their skills in identifying mushroom species and in mycological research. These people often work closely together with the museums of natural history. In 2016, an extensive Sieniatlas (mushroom atlas) project was launched by museums of natural history and the Finnish Mycological Society. Its objective is to gather information about the distribution of mushroom species, their habitats and endangerment. The project collects the observations of both hobbyists and researchers into a database that can be freely utilised by anyone.

By 2022, tens of thousands of civic observations have accumulated. The reliability of audience observations varies depending on the submitter's basal knowledge, so the data from Sieniatlas is reviewed by experts.

The background and history of the tradition

The current Finnish mushroom picking culture has spread to Finland from two different directions. In Sweden, the mushroom dish culture returned in the late 19th century, when the French Jean Baptiste Bernadotte became the King of Sweden, taking the name Karl Johan XIV. Like his countrymen, he has a taste for ceps, which is why the mushroom received a nickname ‘karljohan’. The Swedes brought the use of boletaceae and chanterelles to Western Finland.

In Russia, using mushrooms for food has been much more common than in Finland. Utilising ‘milk mushrooms’, i.e. lactarius species, spread to Eastern Finland from behind the border. When the Karelian evacuees moved to different parts of Finland after the wars, this promoted the spreading of eastern mushroom traditions and the merging of eastern and western mushroom traditions.

Harvesting mushrooms for food requires a much more careful approach to identification of species than picking berries, for example. Of the thousands of mushroom species growing in Finland, a few dozen are poisonous to humans. Identifying mushrooms is a skill that has mostly been passed down the generations as oral tradition, and even today in Finland the majority of Finns received their first lessons regarding mushrooms from their families or relatives. The first Finnish mushroom guide, ‘Sienikirja eli Sieni-Kallen osviitta tuntemaan ja käyttämään syötäviä sieniä’ (Book of mushrooms i.e. Mushroom-John’s guide for identifying and using edible mushrooms) by E. Hisinger, originally written in Swedish, was published in 1860.

The most notable pioneer of mycology in Finland was P. A. Karsten. His magnum opus, published in 1871, was the over 1,000-page long ‘Mycologia Fennica’, which presented up to 1,662 species of mushroom. After Karsten, Finnish mycology stopped for a long time. It was not until 1947 that Professor Toivo Rautavaara published his thesis about the mushroom yield in Finland. A year later, the Finnish Mycological Society was established and it is still in operation today.

In addition to mushroom associations and museums of natural history, the Martha organisation has been actively distributing information about mushroom for over a hundred years. The main focus of the Martha organisation’s mushroom information has been the identification of edible mushrooms and sharing of mushroom recipes. During times of scarceness, in particular, Finns were encouraged to harvest free food from the forests.

The transmission of the tradition

Traditionally, people have gone picking mushrooms with family or relatives. Day-care centres and school classes also often arrange mushroom excursions for the children. The mushroom knowledge of adults is promoted by mushroom courses, excursions and exhibitions organised by different associations, museums of natural history, community colleges and adult education centres.

Today, many Finns also look for mushroom information online or through social media. The most popular social media channel in Finland is Facebook, which offers several groups dedicated to mushrooms and mushroom picking. The most popular of these is the public group of the Finnish Mycological Society, which had over 22,000 members in April 2017. The purpose of the group is to encourage the people in determined, responsible learning of species. The group can be very busy, especially in autumn, and the group members can publish hundreds of pictures a day on the group’s wall. Most threads start with a request to identify the species. However, the discussions emphasise that no one should eat a mushroom they picked just on the basis of photo identification done through a Facebook group, but that real identification is based on careful practice, preferably with the help of experts and literature.

The future of the tradition

In recent years, mushroom picking seems to have grown gradually. The trend of utilising local food and natural products has grown and this also applies to mushroom picking. In 2000, about 38% of Finnish adults reported mushroom picking as a hobby. Ten years later, this number had grown to 43%.

Mushroom picking is still more popular in Eastern Finland than on the west coast, but, on the other hand, the popularity of the hobby has grown rapidly in Western Finland in recent years.

The communities behind the submission

Kuopion luonnontieteellinen museo

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Links

Elintarviketurvallisuusvirasto Evira 2016. Kauppasienet. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Härkönen, M. 2013. Myrkkysienisoppaa. Suomen Sieniseura: Myrkkysienet. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Korhonen, J. 2013. Sienten tunnistaminen. Suomen Sieniseura. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Korhonen, M., Palmén, J. & Timonen, T. 2008. Sienten Käyttöarvomerkistö, Sienilehti 60 (2008): 3, sivut 73–75. Suomen Sieniseuran julkaisuja. Linkki sienimerkistöön.

Kuosmanen, A. 2017. Murskusta korvasieneksi – sienineuvonta Emäntälehdessä 1900-luvulla. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Kytövuori, P. 2013. Sienten säilöminen. Sieniseura. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Palmén, K. 2013. Sienivärjäyksen historia ja alkeet. Sieniseura. - Viitattu 24.4.2017.

Sievänen, T. & Neuvonen, M. 2011. Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010. Metsäntutkimuslaitos. (pdf)

Litterature

von Bonsdorff, T., Hopsu-Neuvonen, A., Huhtinen, S., Korhonen, J., Kosonen, L., Moisio, S. & Palmén, J. 2013. Sienimetsästä markkinoille. Opetushallitus.

Holmberg, P. & Marklund, H. 1998. Sieniopas. Otava.

Jäppinen, J. Kirsi, M. & Salo, K. 1985. Luonnonvaraisten sienten sadot ja kaupallinen poiminta Itä-Suomessa, ensisijaisesti Pohjois-Karjalan läänissä. Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja 200.

Korhonen, M. 1984. Suomen rouskut. Otava.