Puppetry

| Puppetry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

In the early 2020s, Finnish puppetry is undergoing a highly dynamic phase, with three generations of operators working in the field in professional theatres, solo actors and amateur groups. Traditional and new puppetry thrive side by side, and there are both national and international festivals held in this field around Finland throughout the year. Thesises and dissertations have been written on puppetry, and several works of literature about the field have also been published in the 2000s. Puppetry is now more popular than ever before in its history: the more than 3,500 shows staged around Finland are attended by more than 250,000 visitors annually. Outside of statistics, shows are given by dozens of independent puppet theatre groups and solo artists as well as numerous amateur groups.

The Finnish puppetry field is very broad, and hundreds of professionals and amateurs operate within it. Every year, shows are prepared and performed in professional theatres and groups, day care centres, schools, libraries, parishes, elderly care and among immigrants. Puppetry is also used in many ways in e.g. museum pedagogics, art education, therapy and other fields. Puppetry penetrates all layers of society and is aimed at all age groups. Both traditional and contemporary puppetry live side by side. There are three generations of puppeteers who also train and guide new puppeteers, hold courses and spread puppetry as a form of art both in Finland and through touring abroad. Finnish puppeteers have networks all over the world through their international activities.

At present, Finland has three puppet theatres founded in the 1970s that receive state subsidies (Hevosenkenkä Theatre, Teatteri Mukamas and Puppet Theatre Sampo), one party that receives a three-year operational subsidy for performing arts (the Aura of Puppets network, which gathers puppeteers in the independent arts sector together) and two operators founded at the turn of the 2000s that receive discretionary state funding (Puppet Theatre Akseli Klonk and the multidisciplinary Black and White Theatre). In the independent arts sector, there are more than ten puppet theatres founded in the 1980s and 1990s as well as almost fifty groups and solo theatres founded in the 2000s. Additionally, there are numerous working groups active in the field of puppetry that operate either on a production basis or for longer periods of time, as well as working groups with a changing composition that comprise professionals in the field and creators in various fields of art. There are dozens of independent professionals in the field who work in individual productions as freelancers and in theatres as directors, scriptwriters, actors, set and visual designers, puppet makers and in other professional roles. At present, there are roughly 160 professional artists working in the field, of whom the majority have graduated from the Puppetry Department of the Arts Academy of Turku University of Applied Sciences. Even though higher education in puppetry has now been discontinued as its own education programme it is possible to incorporate courses focused on puppetry in the Degree Programme in Drama Instruction.

New consortiums that gather dozens of professionals under their umbrella have been founded in this field: the previously mentioned Aura of Puppets (founded in Turku in 2009, originally under the name Puppet Studio) and Metropolitan Puppets (founded in Helsinki in 2018), Network for qualified in practice (founded in 2019 in Kuopio, nationwide) as well as Lapin nukketeatteriyhdistys (the Puppetry Association of Lapland, founded in Rovaniemi in 2007), which has both professionals and amateurs as members. Six regional artists of puppetry have worked around Finland in the 2000s, promoting puppetry in their areas of operation with many projects and training, among other things. Additionally, numerous Finnish puppeteers work in international projects and foreign puppet theatres. Puppet shows are performed in almost all municipalities in Finland by hundreds of amateurs, and numerous amateur puppet theatres also employ professionals in this field. Since 2000, professionalism in the field of puppetry has also been possible to gain through vocational qualification, accomplished in real production environments. At the moment (2020), puppetry is part of the vocational qualification for performance and stage technology, provided by SAMIedu - an upper secondary vocational education college in the town of Savonlinna.

At present, there are a total of nine Finnish and international puppetry festivals in Finland, in addition to which the repertories of many other festivals feature a great deal of puppetry. International activities are active regarding both art and training. UNIMA Finland (founded in 1984), the Finnish national centre of the International Puppetry Association (Union Internationale de la Marionnette, founded in 1926), promotes the rights of the whole field and serves as an information centre. The organisation’s members include more than 200 puppetry professionals, amateurs, students, researchers and supporters from all over Finland.

Practising of the tradition

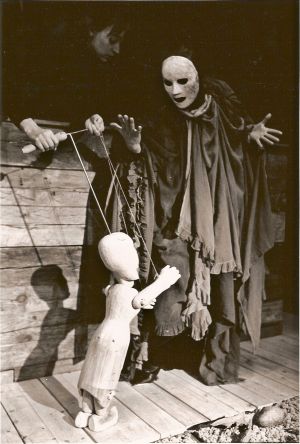

Numerous operators of different types offer puppet theatre performances with a variety of techniques and themes. The types of shows performed on and outside the stage include puppetry, object theatre and shadow puppetry as well as object-centric performances, visual theatre and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary performances. Circus, contemporary dance and even fire art are being incorporated into shows, and a puppet opera was staged in Pori, for example. Traditional puppetry has been joined by forms of contemporary, multidisciplinary puppetry and visual theatre, which have begun attracting new types of audiences, particularly adults, to performances in the 2000s. However, puppetry aimed at children is often the mainstream of this field of art. Additionally, a great deal of applied, community and pedagogical puppetry is being created in this field. There are also activities and operators focused on puppetry in the Taikalamppu network and children’s cultural networks in different parts of Finland. In the amateur field, puppet theatre performances are created and used in day care centres, parishes, schools and libraries, among other places.

In addition to the contemporary forms, traditional puppetry for children is still alive and well in Finland. Subjects are drawn from fairy tales, stories and myths as well as classics and new texts. Old and new professional theatres and groups, as well as solo theatres, explore new approaches and examine the magical world of animation. Shadow play and object theatre are being performed alongside traditional hand and rod puppet and marionette shows. Productions also use means of expression from visual and physical theatre and dance theatre. Institutional theatres produce large-scale shows, with the most recent of them being The Kalevala, a collaboration between Åbo Svenska Teater, Novia and the Arts Academy of Turku University of Applied Sciences, in which the extensive means of expression of puppetry flourished in the hands of almost 30 performers and musicians.

Puppetry is performed at institutional theatres, on independent stages, in dance theatres and on circus stages. Puppet theatre is increasingly performed outside the stage in places such as art galleries, nursing homes and reception centres. Puppet theatre is also created and used for many other purposes, such as art education, therapy, care work, work with immigrants, early childhood education, elderly care, museum pedagogics and teaching.

The background and history of the tradition

Puppetry is one of the oldest forms of theatre, which has spread all over the world. Its development into its own form of theatrical art was preceded by the use of puppets or idols in ancient rituals and later in religious ceremonies. Finns have had their own holy figures: idols shaped from clay and amber, wooden sprite figurines and siedis in nature were worshipped for a long period of time as spirits in material form, even concurrently with Christianity. Through markets and trade, all types of travelling performers came to Finland. Among them were puppeteers, who may have given a push for the creation of Finnish puppetry in the 17th and 18th centuries. However, no documentation of this has been preserved in the field of theatre.

European market theatre and puppetry started to be seen in Finland at the beginning of the 19th century. The repertoires of entertainers travelling from Stockholm to St Petersburg featured mechanical puppets, trick puppets called metamorphoses and mechanical theatre shows called Theatrum Mundi. Around this time, bourgeois and educated families in Finland began to perform marionette, hand puppet, toy and shadow theatre for the children’s amusement. Puppetry also became a pastime for adults: in the 1890s, shadow shows were created in artist circles in large cities and Russian garrisons, drawing inspiration from shows seen abroad.

Professional puppetry was launched in Finland at the beginning of the 20th century: Marionett-teatern, which was primarily intended for adults, was founded by Kalle Nyström in Helsinki in 1909, while Bärbi Luther performed shadow shows for children from 1915 until 1974. The tradition of market theatre was continued by circus artist Arvo Avenius, whose Marionettiteatteri Fennia (Marionet Theatre Fennia) was part of the equipment of carnivals that travelled around Finland in the 1930s and 1940s. The puppet theatre of the Police, which toured schools starting from 1952, provided attitude education to enhance traffic safety. In the 1960s, Irja and Matti Ranin’s Kasper-teatteri (Kasper Theatre) produced a repertoire aimed at children. It performed on television, in short films and on tours. Gunvor Ekroos started Haiharan nukketeatteri (Haihara Puppet Theatre) in Tampere in 1969. New puppetry was seen in Finland at the turn of the 1950s, when the country was visited by both the French Jacques Chesnais and Russian Sergey Obraztsov. Their shows inspired Finnish puppeteers, including Annikki Setälä (Lapin nukketeatteri, Lapland Puppet Theatre) and Mona Leo (Helsingin nukketeatteri, Helsinki Puppet Theatre). The forerunners in puppetry toured Finland by train, bus and taxi – and even by sleigh pulled by reindeer in Lapland. The shows were held in schools, day care centres and hospitals as well as other premises.

At the beginning of the 1970s, professional actors, directors, set designers and dramaturges became involved in creating theatre for children and developing puppetry. New professional puppet theatres Vihreä Omena, Hevosenkenkä, Sampo, Peukalopotti and Teatteri Mukamas threw themselves into their field of art by experimenting with different means of expression. Puppet shows were also performed in several institutional theatres around Finland. Dozens of amateur groups were founded around the country, and the longest-standing of them continued their activities for several decades. In the 1980s, more than 10 professional solo puppet theatres and small groups were founded in different parts of Finland. At the turn of the 1990s, puppetry activities were very active all around Finland, and numerous new puppet theatre groups were once again founded in different parts of the country. Among them was Akseli Klonk, a puppet theatre founded in Oulu that has also operated Junateatteri (Train Theatre) for several summers. At the turn of the millennium, the Finnish puppetry field expanded many times over when numerous professional puppet theatre groups were founded as a result of puppetry education being provided at the University of Applied Sciences level. The majority of them set out to create contemporary puppetry. Multidisciplinary and modern puppetry and object theatre use new aesthetics, techniques, themes and dramaturgy in productions. New puppetry aimed at adults, as well as avant-garde and interdisciplinary art, are part of the present.

The transmission of the tradition

There are artists from three different generations operating in Finland, who each contribute to the passing on of puppetry art and its development as a living and thriving art. Professionals in the field teach, train and pass on their knowledge and skills as mentors. In Finland, puppetry education and courses are provided e.g. at the Arts Academy of Turku University of Applied Sciences, and courses are taught by professionals at community colleges and Uniarts Helsinki’s Theatre Academy, among other places. Vocational qualification in puppetry can be accomplish in SAMIedu vocational college.

Every year, Finland also hosts numerous seminars, lectures, workshops and other events that examine questions related to art. Festivals are a part of the passing on of puppetry art to the general public. Additionally, the operators in the field direct their activities and connections towards the decision-makers in the cultural sector and other parties in order to enhance and increase the significance and understanding of puppetry.

The Theatre Museum has accepted items and publications related to the field of puppetry. Puppet theatres that operate or have operated in different parts of Finland have been and will continue to be urged to preserve their collections of items and documentation through local memory organisations. Additionally, the eldest generation is urged to write down their histories and biographies. The organisations mentioned above are in charge of the collections. UNIMA Finland seeks to stay up to date on the recording of the field.

The future of the tradition

Finnish puppetry is in its heyday, and new generations continue to develop the field strongly. Puppetry art has always affected the surrounding society both artistically and by challenging and breaking conventions. Puppetry has influenced millions of spectators in Finland and taken the art’s humanistic message forwards over the course of its more than 110-year history. Contemporary puppetry has tackled hot topics and roused both its audience and decision-makers with its interpretations. The diversity of Finnish puppetry is a strength that is helping this form of art break through to the frontline of art.

In Finland, puppetry has expanded in terms of art, education and quantity over the 2000s, becoming a significant actor in Finland and at the international level. Puppetry meets all the characteristics of the field of performing arts, but in terms of resource allocation, it has been left on the side lines. Puppetry is not yet at the same starting line with the operators in other performing arts regarding the distribution of public financial aid.

The field of puppetry is in a financially unequal position compared to the field of performing arts as a whole: in 2012, professional puppet theatres had more than 2,700 officially recorded performances, which account for 14% of all theatre performances recorded in statistics that year. The puppet theatres included in statistics received 0.2% of the public appropriations for performing arts. There are also dozens of professional operators left outside the statistics. None of the dozens of puppet theatre operators in the independent arts sector have been able to enter the funding system guaranteed by the Theatres and Orchestras Act since 1993. The field requires more public funding and resources, in addition to which professional puppetry must be strengthened, and the visibility, accessibility and appreciation of puppetry must be increased. The development of the field of puppetry and the securing of its future play a key role in ensuring the conditions for operating in the field, which are in an almost critical state regarding independent operators.

UNIMA Finland prepared an official report to the Ministry of Education and Culture on the state of the field of puppetry and the required measures in 2013. The organisation has also turned to the Arts Promotion Centre Finland, Theatre Info Finland and other official parties. Influencing efforts have been continued intensively for over five years. A project called Sukupolvien kohtaaminen (Meeting of Generations) is currently being planned. In this project, the three generations in the field will work together to pass on their knowledge and skills and to promote the future of the field. The most important tasks in the field of puppetry in the near future are increasing funding and securing education in this fragmented field of limited resources, developing regional operations, improving cooperation and communications, strengthening production expertise and employees who specialise in it in the independent arts sector as well as forming networks in Finland and at the international level. Education in the field, at all levels, is critical for the whole field’s development. The future of higher education in puppetry must be secured, and education should be provided at the level of both a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree.

The communities behind this submission

Suomen UNIMA ry, advocacy organisation in the field of puppetry

Nukketeatteritaiteilijayhdistys Aura of Puppets

Private individuals: Eero Siren, Anna-Liisa Tarvainen

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Web-links:

International puppetry festival TIP-Fest

Finnish modern puppetry festival Oh my puppets!

Literature:

Nukketeatteria suomalaisilla näyttämöillä (LIKE 2009).

Writings and articles of Maiju Tawast.

AROPALTIO, Kirsi et al. Nukketeatteri ja naamioleikit. Helsinki: Otava, 1979.

ANDRIANOV, Katriina. Esine roolissa. Doctoral thesis. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto, 2015.

BARIČ, Bojan - AUVINEN, Suvi. Sateenkaaren päässä – YK:n vuosituhatjulistus ja nukketeatteri. Helsinki: Ministry of Foreign Affairs Finland, 2007.

BARIČ, Maija - Kristiina Louhi. Nukketeatteria! Helsinki: Nukketeatteri Sampo, 1997.

BARIČ, Maija - Kristiina Louhi. Puppet Theatre! Helsinki: Nukketeatteri Sampo, 2004 (Nukketeatteri Sampo has also published many books, cd-discs and other material).

FALKE, Ishmael. Carrot, sticks and a Black Box - A Guide for the Practise of Contemporary Puppet Theatre. Turku: Sixfingers Theatre, 2011.

FALKE, Ishmael. Keppi, porkkana ja musta laatikko! – nykynukketeatterin opaskirja. Turku: Sixfingers Theatre, 2011.

HILTUNEN, Mirja - TORNIAINEN, Liisa (toim.). Naamionuken monet kasvot – Nukketeatteri yhteisöllisenä taidekasvattajana. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland , 1998.

HIRN, Sven. Nukketeatterimme varhaisvaiheet. Helsinki: SKS, 2010.

KOKKONEN, Saara. Nukketeatteri elää. Helsinki: Kirjastopalvelu, 1982.

NÄTTILÄ, Pertti – KINNUNEN, Raimo J. Ransu karvakuono. Helsinki: WSOY, 2002.

PELTONEN, Leila - TAWAST, Marjut (toim). Nukketeatteria suomalaisilla näyttämöillä. Helsinki: LIKE, 2009.

PELTONEN, Leila - Nukketeatterin tekijänä Lapissa – pohjoista nukketeatterikulttuuria 1940-luvulta tähän päivään (Atrain&Nord 2019).

PYYSALO, Katri. Kaikenmaailman Kasperit – nukketeatteri museonäyttämöllä. Tampere: Nukke- ja pukumuseo, 2001.

RIIKONEN, Mervi. Värien ja varjojen näyttämö. Tampere: Cityoffset oy, 2000.

RÄISÄ, Hannu. Nasty Puppet nukketeatteritekniikoita. Helsinki: Johnny Kniga, 2009.

SIPPOLA, Outi: Elotonkin liikuttuu. Turku, Aura of Puppets 2016.

SIREN, Eero. Nukketeatteri ja näyttelijän maailma. Väitöskirja. Helsinki: The Theater Academy of Uniarts Helsinki, 2017.

MUURINEN, Teija, VÄNTSI, Timo ja WITTING Sari. HOKSNOKKA Kirsti Huuhkan nukenrakennusohjeita. Helsinki: Draamatyö, 2012.

NB: More literature can be found in "Nukketeatteria suomalaisilla näyttämöillä" pp. 317 – 320.