Runeberg celebrations

| Runeberg celebrations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

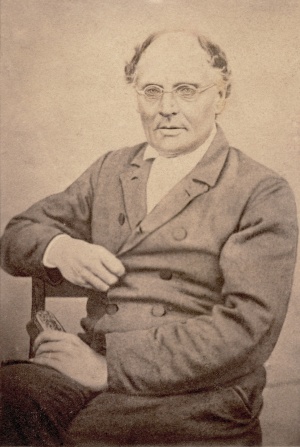

Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s poetry has touched many people, on both a personal and emotional level. Older generations in particular are familiar with works such as The Tales of Ensign Stål featuring characters including Sven Dufva and Lotta Svärd. This book could be found in most homes during the first half of the 20th century. Runeberg’s lyrical and epic poems, above all Farmer Paavo, played a key role in the creation of the image of the Finn as a hard worker, faithful, honest and devout, an image that to some extent still exists in public opinion.

After World War Two, the popular image of Runeberg and his work changed radically. This re-evaluation was a consequence of the changing zeitgeist. The new social movements that finally took hold in Finland, including pacifism, the solidarity movement, the left-wing movement and the women’s rights movement meant that this romanticised and idealistic image of Finland and its population that Runeberg had stood for began to fall out of favour. Runeberg began, instead, to be seen as a warmonger and oppressor of women.

Despite this, Runeberg has retained his position as Finland’s national poet. The image of Runeberg has gained other focuses instead. There is also a great deal of interest in his wife, the author and feminist Fredrika Runeberg.

Naturally, Runeberg’s memory is celebrated in Finland, both as a national holiday on his birthday, 5 February, but also in a more popular sense. His memory has also been celebrated in Sweden, and songs set to his texts are often seen in Swedish song books, including Finland’s national anthem Our Land, which was commonly sung in Sweden up until the 1960s.

Practising of the tradition

The changing perspective on Runeberg and new social conditions also created completely new traditions based on old foundations. Dotted around Finland were places people made pilgrimages to in order to remember Runeberg or historical events he had described. Since the 1970s, and in particular in the 2000s, tourism and the local heritage movement have brought new life to these places, both physically on the ground and online. Visitors are offered historical food, theatre, music, opportunities to step back in time, films and games, and events such as festivals, seminars, discussions and meetings are organised on topics related to Runeberg, his times and his works. Since 1993, the area around the site of the Battle of Oravais has been built up into a comprehensive tourist experience, based on characters from The Tales of Ensign Stål, including Wilhelm von Schwerin, who died in battle in Oravais. Porvoo Museum also has a century-long history of activities relating to Runeberg, and is responsible for maintaining Runeberg’s home as a museum – Finland’s first home museum – founded in 1885.

Furthermore, for many years there has been an abundance of so-called Runeberg sites throughout the country, including Vestmansmors stuga (Runeberg’s school) and Runeberg’s hunting and fishing cabin in Jakobstad, the soldiers’ cottage in Ytterjeppo, Torgare rectory and kärleksstigen path in Kronoby, Fredrikastugan cabin and Runeberg’s spruce in Pargas, Runeberg’s spring in both Ruovesi and Kroknäs, and Runeberg’s grave in Porvoo. All of these historical sites are staffed by guides who maintain a storytelling tradition focused on historical events. Stories, combined with being physically present in a place, give a visitor a sense of historical proximity. These events form part of a greater context that gives meaning to the experience, and the stories contribute, therefore, to shaping a common collective memory.

All of the streets, restaurants, cafés, etc. around Finland named after Runeberg, the heroes of his poems or Fredrika Runeberg also help keep the history alive.

Runeberg Day is generally marked with a morning assembly at schools throughout Finland, regardless whether the teaching is provided in Finnish or Swedish. Sometimes more in-depth presentations about the national poet’s life and works are also given. On the Finnish-language front, Mauri Kunnas’s picture book Koiramäen Martta ja Ruuneperi (‘Martta and Ruuneperi of doghill’) has also helped to bring to life this man of distinction for younger generations. Runeberg’s texts have also been preserved in the world of Finnish music, including psalms in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland’s psalm book, and in a whole range of songs and compositions by the likes of Jean Sibelius, including Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte (‘The girl returned from meeting her lover’). However, the most commonly sung song is most likely Finland’s national anthem, Vårt land (Fi. ‘Maamme’, En. ‘Our Land’), which makes an appearance at popular folk celebrations, in nationally significant contexts, and at international athletics events when a Finn has won a gold medal.

The background and history of the tradition

During the 19th century, views on Finland’s national poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg were largely controlled by an educated elite class, who shaped how the national poet would be perceived and celebrated. Knowledge about Runeberg and his poetry was communicated to the public, partially via schools, and partially via associations formed for the purpose of public education.

However, there were also critical voices, even before World War Two. Whilst Runeberg’s position as a national poet may not have been questioned, some disliked him as he was considered too noble and elitist. Schools forcing pupils to learn certain parts of The Tales of Ensign Stål by heart was considered unnecessary and onerous. At times, questions have also been raised as to why Finland should have a Swedish-speaking national poet and a national anthem not originally written in Finnish. However, amongst the public aon the whole, Runeberg’s memory has been considered important, with one example being the naming of the Lotta Svärd organisation after a fictional character in The Tales of Ensign Stål.

In 1935, historian of ideas Yrjö Hirn created a concept for the celebration of the national poet and his memory, through the book Runebergskulten (‘The Runeberg cult’). The poet got his breakthrough in the first part of The Tales of Ensign Stål, which was published in 1848. However, Runeberg became the national poet for the entire Finnish population in the 20th century through the nationalist agenda developed by the ‘people’s school,’ whereby Runeberg, with the help of pedagogue Zacharias Topelius and his textbook ‘Book of Our Land,’ became a prominent figure in Finnish too. The book remained a textbook used in Finnish schools for over 75 years. The poem Our Land was sung for the first time at a student celebration in Kumpula, Helsinki, on 17 May 1848. After that, the song was sung regularly in folk and patriotic contexts, and eventually came to be designated Finland’s national anthem. Since Runeberg’s fiftieth birthday in 1854, he has been celebrated publicly on his birthday each year on 5 February. Runeberg celebrations gradually came to be held throughout the country, and by the mid 1860s the celebrations had taken on an established format, involving patriotic speeches, music and singing in unison.

Gradually, a cake known as the Runeberg torte also became a part of traditional Runeberg celebrations. In 1865, the Helsinki bakery Ekbergs bageri announced that they were selling Runeberg torte; however, the cake’s roots stretch back far further. The bakery Astenius bageri in Porvoo produced the cakes, and as Runeberg, known for his sweet tooth, was so fond of them, they eventually came to be known by his name. On 5 February 1858 – Runeberg’s 54th birthday – the students of Porvoo’s upper secondary school celebrated the day with song for the first time. Following Runeberg’s death, this led to the tradition of sung tributes at the Runeberg memorials in Helsinki, Porvoo and Jakobstad on Runeberg day – a tradition that continues to this day. Candles were also lit in windows, which later became a tradition associated with Finnish Independence Day, the 6th of December, instead. In 1885, the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland was established in Runeberg’s memory, and the Society’s anniversary is celebrated solemnly on 5 February each year.

The transmission of the tradition

The two most visible symbols that remind people today of the national poet are the flag day on Runeberg day, 5 February, and the sale of Runeberg torte, which, in the name of equality, are also now available in the form of Fredrika torte. Many people’s thoughts are also drawn to Finland’s history when the national anthem is sung – a song that all schoolchildren learn. The mass media and social media also feature articles or comments on Runeberg day, reminding us about the national poet.

Runeberg receives only a limited amount of attention nowadays in the home environment. However, some private celebrations are held, often based on family traditions that the family has chosen to maintain. The most common way of celebrating Runeberg is to buy or bake Runeberg torte, which in some cases are eaten in a patriotic atmosphere, like a small ceremony or an eccentric and entertaining Finnish tradition. One area that does receive plenty of attention is the prizes awarded to researchers and authors on Runeberg day, at the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland’s annual celebration in Helsinki and at the literary Runeberg Prize and Runeberg Junior Prize ceremony in Porvoo.

There are also a great number of other associations, institutions and societies who organise different kinds of celebrations on Runeberg day. Long gone are the days when the festivities were intended to venerate the poet, and instead events today focus on the significance of literature, music and culture in society.

The future of the tradition

Previous generations were well-acquainted with many of Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s literary works. If a person wished to give weight to their view, it was common practice to weave a Runeberg quotation in their speech, either as a faithful quote or paraphrased. Popular options included ‘den kulan visste hur den tog’ (‘It knew precisely where to strike, that little ball of lead’) or ‘ett dåligt huvud hade han, men hjärtat det var gott’ (‘His head was bad, was Dufva’s, but his heart, now – that was good’), both from the poem Sven Dufva. Nowadays, such a broad knowledge of the poems of the national poet is not as common. However, the themes interwoven into Runeberg’s works are particularly relevant today. Runeberg day could be, and already is to some extent, a day when it feels natural to contemplate citizenship in relation to globalisation and internationalisation, a day when discussions about symbols, patriotism, culture and literature take place within a national frame of reference.

A similar theme also forms part of Kalevala Day, and in particular Independence Day, however Runeberg Day has its own profile due to the fact it is the birthday of the national poet.

The Runeberg Week is held annually in Jakobstad, a week of culture in honor of Johan Ludvig Runeberg. During the week, Jakobstad is visited by authors in different events, both public, as in schools. Runeberg Week has approximately 4 000 visitors each year, and the program includes also music, theatre and discussions.

The community/communities behind this submission.

The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, Porvoo museum och Jakobstads cultural office

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Anne Bergman: Runeberg i folktraditionen. Källan 1/2004 s. 38-50

Svenska litteratursällskapets arkiv, Helsingfors, SLS 2017 ”Runeberg och andra nationella hjältar”, Anne Bergman 2002.

Hirn, Yrjö, Runebergskulten, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsingfors 1935

Rahikainen, Agneta, Johan Ludvig och Fredrika Runeberg. En bildbiografi, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsingfors 2003

Rahikainen, Agneta, ”Runeberg, männen och fosterlandet. Några synpunkter på Svenska litteratursällskapet och Runebergskulten”, Historiska och litteraturhistoriska studier 85, Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, Helsingfors 2010