Sailing on traditional clinker boats

| Sailing on traditional clinker boats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

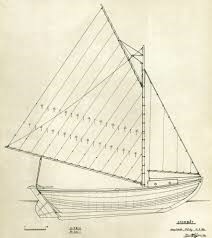

Traditional clinker boats have been used for sailing for a long time. Their development has evolved from square sails to sprit sails and on to gaff riggings. The first masts were sometimes constructed using small deciduous trees cut from the shore and held upright to provide boats with speed in a tailwind. The smallest boats did not have sails.

Traditional open clinker boats have been used for recreational sailing in Finland’s coastal and archipelago areas for a long time. They were already used for this purpose by a few people back when the islanders were still utilising their boats for fishing and transportation, i.e. their original purpose. In addition to the traditional boats, pleasure craft with sails are still produced using the clinker boat method of overlapping planks. These boats are sailed and used the same way as modern fibreglass sailing boats.

The majority of these former work horses of the archipelago have always been privately owned. Still today, these boats are privately owned recreational vessels that are used to make short trips or even spend the entire summer holiday on. Some boats are also owned by associations, in which case their purpose is to provide interested people with a chance to try out sailing following the traditions of previous generations. The associations also provide training to children and young people on the traditional sailing skills and the everyday chores of our ancestors.

Sailing is a popular pastime among both the local population and holidaymakers in the coastal areas and the archipelago. These population groups work together in the related associations and during sailing events. This serves to increase their sense of solidarity.

The purpose of the modern use of open clinker boats is to create some sort of a connection for the coastal and island population with the old culture and to learn about living by the sea and navigating the waters. Currently there are about 200 traditional clinker boats in good sailing condition in Finland. This number does not include wooden pleasure craft with keels, such as the folkboat. In addition, there are just under ten organisations that can be classified as traditional boat associations. Many ordinary boat clubs have a special division that focuses on upholding traditional sailing practices. Some associations also focus on managing museums.

Practising of the tradition

Boat use and sailing can be divided into two distinct categories that differ remarkably from one another. Around a dozen competitions are held for these boats during the summer holiday season. The most enthusiastic competitors tow their boats from one competition to the next, craving victory. These competitions have had a significant impact as old boats long since decommissioned have been restored and relaunched. The repairs performed on old boats have had an effect on the preservation of boat building skills. The competitions have always attracted large audiences, and while the boats are moored, they can be viewed from close up. When the sails are hoisted, the audience can watch the boats sailing and usually follow the competition from the shoreline and piers.

A completely different group of users is formed by those people who have chosen these open clinker boats as pleasure craft. They use the boats to make day trips, enjoying the fine weather during the summer holiday season. The larger boat types are equipped with a small cabin, making a multi-day or -week sailing holiday easier, because accommodation is always available. These boats are normally gaff rigged and can easily be managed by a single person, similarly to the smaller vessels. The larger boats also motors as a special feature, which provides a certain sense of security and eliminates any challenges caused by calm weather, thereby ensuring, for example, that pre-determined schedules can be kept.

Vinden Drar is a notable Nordic event that was established by sailing enthusiasts in Åland. Since 1985, approximately 200 Nordic clinker boat enthusiasts have been spending a week together in July under the flag of Vinden Drar. This event has been organised annually, and hosted in turn by Åland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Faroe Islands. The event has been held in Finland three times, and the next one will take place in 2018. During the week, the participants have a chance to sail on other Nordic clinker boats and learn about their special features. The week’s programme includes lectures and traditions connected to the archipelago’s culture, with the clinker boat being at the heart of the activities.

In principle, sailing is easy. If you have sailed a vessel such as a small optimist dinghy as a child, you will learn to control a traditional boat in a few hours. Sailing a traditional boat and a modern fibre glass boat follow the same logic: people who can get a traditional boat to move exceptionally well will also quickly learn how to maximise the speed of a fibre glass boat.

The background and history of the tradition

The ability to sail is technically as old as travelling on water by boat. People in the archipelago have been sailing and rowing boats for as long as these areas have been inhabited. Windward sailing with a square rig was ineffective and therefore not even attempted, and instead people would row or wait for the wind to change direction. Furthermore, the Church and priests were not keen on boats that could move against a headwind, because they thought they were the creation of the Devil. Water causes little friction.

Because there were no highways, travelling across water was natural, both at sea and on lakes. A boat was a necessary and self-evident thing to have. They were used to fish, gather leaf fodder and hay from islands, travel to the pasture islands to milk the cows and transport grazing cows and sheep. Boats took people to towns to sell their fish and other produce, and on Sundays, they would sail to church.

During the end of the 19th century, the gentlemen of Turku’s Airisto Segelsällskap sailing club would watch these boats being sailed by the people from the archipelago, viewing their rigging as primitive. The inhabitants of the archipelago were sailing to Turku to sell their produce to the town’s residents, giving the amateur sailors in the town an opportunity to observe their boats and their crude rigging. As early as in the 19th century, the gentry decided to begin organising an annual sailing competition with these archipelago boats. This tradition still continues, although since the 1950s the boats attending the competition have not been used for other purposes than for racing. In other words, the competitions were launched by city-dwellers. The competitions have led to the foundation of several traditional boat associations in the archipelago. The ordinary boat clubs operating in the archipelago have also included clinker boats in their activities through sailing competitions and other events. They organise boat building courses and teach people how to sail, maintain and repair boats.

The transmission of the tradition

The skill of sailing traditional boats is often passed on from parents to children. Events and competitions seem to be the best way to continue the tradition. Competitions are held along the coast from Loviisa to Ostrobothnia. The most extensive activities take place in Turku’s archipelago, where competitions are held at least in Korpo, Nagu, Houtskär, Iniö and Kustavi. A competition start line can have as many as 30 boats. Some competitions have several categories for boats of different lengths. The sail material can also have an effect on which category a boat belongs in. Many associations also have strict written rules to keep the boats in as original a form as possible. Sailing competitions are fun events. The competitors have realised that a long waterline and large sails are beneficial in a race. However, being a skilled sailor, having an experienced crew and sailing in familiar waters may prove more valuable than a large sail size. Although these are friendly competitions, they do become fairly serious at the sounding of the start signal. After the race, however, the crews are always back to being friends. Everyone already knows one another. The number of spectators can amount up to 500 people. Competitions are often held together with other summer-time events so that the spectators can enjoy entertainment all day long till the evening dances.

New boats vary significantly in price. For example, a six-metre boat with 12 siding planks and bent frames might only be half the price of a similar size boat with six siding planks and naturally curving frames. A boatbuilder can fit the bent frames in a single day, while searching for naturally curving roots and branches in the forest may take a month and fitting them in perhaps another two. New boats are, therefore, expensive, which clearly hinders the tradition’s popularity from becoming more widely spread. If a family can afford only one boat, it is likely not going to be an open clinker boat for sailing.

The future of the tradition

The current trend of green thinking may be creating a new generation of people who want their boats to be made of wood and other natural materials. A boat made from such materials will not become hazardous waste or an environmental risk after being in service for a few generations. Clinker boat enthusiasts thought that the new environmentally aware generation was going to favour boats built by using the tradition method and powered by the wind. However, this has not happened, and one of the reasons is most likely the high manufacturing cost. For the price of a new traditional boat you can get a used fibre glass sailing boat with all the extras. And if you decide you no longer want to continue sailing, a fibre glass boat is also much easier to sell. Used traditional boats are seldom available for sale, and the potential group of buyers is also limited. Attempts are being made to preserve the sailing tradition by organising courses and events.

The main threat to the practice in addition to the steep price of a new boat is probably that despite maintenance, the condition of many boats in use will slowly deteriorate to a point where the boat cannot be used anymore. Replacing rotten planks or frames, not to mention the keel plank, is laborious and time consuming, if the owner wants to use a professional. If the number of boats falls significantly, numbers of sailmakers skilled in the old traditional methods may dwindle. Furthermore, it is not easy to find suitable sailcloth material for these boats, and the same goes for the rigging. Activities conducted within and between associations is a good way to uphold the hobby.

It is likely that the tradition will remain fairly unchanged. There will always be people who want to blaze their own trails and learn the traditional boatbuilding methods, despite knowing that orders will be few and far between. It is also extremely likely that these boats that the previous generations used for work will have their purchasers and users in the future, as well. These people are not ‘sailors’ but individuals who are so fascinated by the traditional lifestyle and culture of the coast and archipelago that they want to be physically part of that lifestyle during their free time. These people are the potential buyers of new boats and upholders of the tradition. Continuing the competitions is also key, because these events can reach people who themselves may not necessarily want to own open wooden boats but who appreciate the fact that traditions are being kept alive. Education in building of clinker boats is provided, for example, by Livia Vocational School in Parainen, Eurajoki Christian College and Kuggom Traditions Center in Loviisa.

On December 2021, the Nordic clinker boat tradition was inscribed to UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The application was the first multi-national file made by the Nordic countries, and a few hundred operators in the sector were involved in the process, including boat builders, associations, museums and education providers. A total of 19 Finnish communities operating in the field supported the submission of the nomination. Being added to UNESCO’s list gives recognition to the Nordic handicraft tradition and work towards safeguarding the wooden boat heritage in the northern regions. The application process has already led to the initiation of various projects connected to this tradition around the Nordic countries.

The communities behind this submission

NGOs

Bosund båt-, fiske- och jaktmuseum ry

Finnish Wooden boat Builders rf

Gip-Jiippi (Yhteenliittymä)

Houtskär Allmogebåtsförening.rf

Kirkkonummen Perinneveneyhdistys St. Nikolaus.ry.

Kotkan Pursiseura ry - Kotka segelsällskap rf

Kustavin Talonpoikaispurjehtijat ry

MYS (Mahogany Yachting Society)

Suomen Puuveneilijät ry Finnish Woodenboat Association

Turunmaan Perinneveneyhdistys ry.

Östnyländs Allmogebåtsförening rf.

Museums and institutions

The Maritime Museum of Finland

Sjöhistoriska Institutionen vid Åbo Akademi

Skärgårdsmuseet (Rönnäs, Loviisa)

Boatbuilders

Marko Nikula, Eero Ranta, Petter Mellberg, Joel Simberg, Jukka Salo, Jukka Viinikainen, Lennart Söderlund, Jan Backman, Veijo Sorvali, Jari Vanhatalo, Erkki Lönnqvist, Allan Savolainen, Riku Nylund

Other experts

Esko Mattsson, Harro Koskinen, Bosse Mellberg, Markku Jussila, Kari Herhi, Juha Herranen, Sami Uotinen, Stefan Hellström, Leo Skogström, Tero Lehti, Tuomas Nuotio, Rabbe Smedlund, Visa Roine, Timo Back, Henry Forssell

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Websites

Puuvenemallisto Woodenboat Collection (FI / SV)

Puuvene.net -keskustelufoorumi

Education in building clinker boats

Eurajoki Christian College, Eurajoki

Adult education centres around Finland

Litterature

Broch, Ole-Jacob 1997. Puuvene - limisauma, tasasauma, ristiinlaminointi, korjaukset ja huolto. Helsinki: Opetushallitus.

Chapelle, Howard 1969. Boatbuilding - a complete handbook of wooden boat construction. New York: W.W.Norton Company.

Föreningen Sveriges Sjöfartsmuseum i Stockholm 1999. Människor och båtar i Norden. Sjöhistorisk årsbok 1998-1999. Borås: Centraltryckeriet Åke Svenson AB.

Klippi, Yrjö & Aromaa, Juha & Klippi, Pyry 2015. Puuvene Suomessa. Helsinki: ReadMe.fi.

Perälä, Osmo 2011. Puuvene – veistäminen, kunnostaminen, perinne. Hämeenlinna: Kariston Kirjapaino Oy.

Pälviranta, Edgar 1997. Veneenrakennuksen oppikirja – lauta- ja rimarakenteiset U-pohjaiset soutu- ja perämoottoriveneet. Helsinki: Opetushallitus.

Rovamo, Pertti & Lintunen, Martti 1995. Suomalainen puuvene. Porvoo: WSOY.

Rössel, Greg 2000. Building small boats. North Brooksville: WoodenBoat Publications.

Simmons, Walter, J. 1980. Lapstrake Boatbuilding. Camden: International Marine Publishing Company.

Törnroos, Birger 1968. Båtar och båybyggeri i Ålands Östra skärgård 1850-1930. Meddelande från Sjöhistoriska Museet vid Åbo Akademi. Nr 11.

Törnroos, Birger 1978. Öståländska fiskebåtar förr och nu. Meddelande från Sjöhistoriska Museet vid Åbo Akademi. Nr 13.