The rya tradition in Vesilahti

| The rya tradition in Vesilahti | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

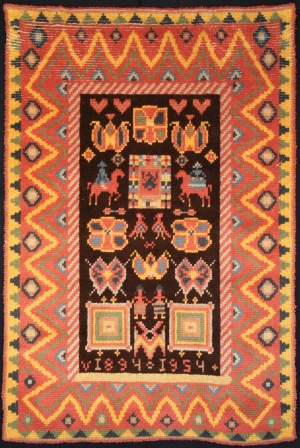

The municipality of Vesilahti in Southern Finland has been known for its ryas for centuries. The tradition has been so strong and productive that a large number of households still have ryas on their walls. The majority of ryas are privately owned. The rya weaving skill has not disappeared from Vesilahti, because many people have a loom at home, ready for weaving, if they have the space. In the past, a rya was an indispensable piece of everyday textile, which is why it ultimately came to be so highly valued and has remained popular among weavers, occasionally even increasing in popularity.

In Vesilahti, the foundation of a cottage industry advice centre in 1976 has significantly affected the preservation and continuation of the tradition, since the centre has several looms that can be used to weave ryas with guidance from experts. Since then, countless locals have learned this skill. Currently the centre functions as a Taito centre and specialises in ryas. A collection, which is constantly receiving new additions, has been created of both traditional and new ryas. A large number of ryas from various periods have been showcased at several exhibitions over the years. In addition, the rya collection can be viewed online. In 2008, rya experts published a book on Vesilahti’s wall rugs.

Practising of the tradition

In Vesilahti, young women used to make bridal ryas for their weddings. Sometimes the bride would weave the rya herself to demonstrate her craft skills. Ryas are still common at summer weddings, placed underneath the wedding couple. The local parish’s wedding rya, Vesilahden tienoot (‘Landscapes of Vesilahti’), was weaved by Raili Hoikkanen in 1955 at the age of 18. The rya has the year 1802 weaved into it, which is when Vesilahti’s current church building was constructed. In 2008, crafts teacher Sisko Laurila donated her version of Vesilahti’s oldest rya from 1701, which was used as a burial shroud, to the parish of Vesilahti.

Other old ryas have also been honoured by making copies and reconstructions of them. One example of these is the rya of Perttuli in Suomela from the 18th century, and as was customary at the time, the rya has pile on both sides. The crafts centre in Vesilahti made a reconstruction of this rya with a total of 44,000 strands of pile. A version without pile at the back was finished in spring 2017.

Ryas have also traditionally been made for local public buildings. In 1996, two pupils at Vesilahti’s comprehensive school upper stage, Heidi Lindell and Ilkka Heinonen, designed a rya named Tiedon aurinko (‘The Sun of Knowledge’) for their school wall. They weaved their rya under the instruction of their crafts teacher, Leena Hellman. A few knots for the rya were also tied by the then First Lady Eeva Ahtisaari.

A short while later, a 100-year anniversary rya, Ameen niinipuut (‘Ame’s linden trees’), was made for the school of Krääkkiö, designed by Tiina Kinnari based on a group of locally famous trees. Apart from the blue colour, the yarn was dyed with plants from the schoolyard.

In 2012, Sonja Valkama designed a rya called Isenge for the school. Narva’s new day care centre, Peuraniitty, received a rug in 2016 designed by Sinikka and Tiina Nopola and called Heinähatun ja Vilttitossun ilmapalloleikki (‘Hayflower and Quiltshoe’s game with balloons’), based on the characters of Finnish children’s stories written by the sisters. Vesilahti’s new library, which was completed in autumn 2017, will have a rya named Tieto ja Tunne (‘Knowledge and Emotion’) by Jukka Vesterinen.

The ryas’ patterns are first designed with watercolours on paper, after which the sketch is transferred on millimetre paper for marking the pile colours. Each square represents one strand of pile to be tied. Traditional ryas used earth tones, while the colour palate of modern ryas follows common decoration trends. Vesilahti’s ryas are very colourful.

Ryas are made on a loom by weaving a base of approximately 1–1.5 cm in thickness with wool yarn and a shuttle passed through the warp that is stretched on the loom. After the midsection weft has been weaved in, pre-cut strands of yarn are tied into a row of pile, in which each strand marked in the sketch is attached around two warp yarns. This knot is called the Smyrna knot. (see photo)

If there is no loom available, ryas can also be made by sewing. In that case a special pre-made base fabric is used to sew in the pile strands with a rya needle according to the sketch. The last stage is to cut the pile.

In Vesilahti, ryas are weaved at the local Taito centre, which also commissions ryas from its home weavers. The locals also use commercially produced material packages accompanied by clear instructions to make ryas by sewing.

The background and history of the tradition

According to ancient tradition, textile making was women’s work. When flax became a more common crop in Vesilahti during the end of the 18th century, people began spending their autumns processing it: the crop was gathered, soaked, broken, and scutched in hot flax saunas. Wool from sheep was also shorn and processed in the autumn. In the winter, both materials were spun into yarn, which was weaved into fabric and ryas in the spring. Originally, the warp was made from durable linen yarn, but over time it was replaced by cotton.

The largest manor house in Vesilahti, Laukko, and a few gentry estates used to spread information and skills related to rya making. Ryas were imported to Sweden from the weaver’s hut of Laukko in the 16th and 17th centuries. The parsonage was also a notable producer and user of ryas.

When life returned to normal after the wars of the 18th century, rya weaving began to increase in popularity. Hired farm workers began weaving them for their masters’ new buildings, which were bright and had chimneys. Tenant farmers would pay their rent partly in the form of ryas. One third of Vesilahti’s estate inventory deeds contain mentions of ryas, although mostly in connection to farm owners – ryas were rare in the dwellings of the rest of the population. The increasing popularity of ryas was also evident in the fact that they were often mentioned at the top of bedclothes lists. Although starting from the end of the 19th century, some ryas were used for warmth during sleigh rides, this does not indicate a decrease in how they were valued. In freezing temperatures, nothing could offer better protection against the cold than a rya, and their rose patterns were also beautiful to look at. Some ryas were weaved to have their colourful backs showing behind benches.

Vesilahti’s ryas exhibit local flavours, the most important of which is the raspberry red colour also used in Vesilahti’s folk costume and most probably made from a plant called the common madder. According to Pehr Adrian Gadd, this plant was likely brought to Finland from Holland by the gentry. Other common colours included natural black and moss green, which started becoming more popular in the early 19th century. Blue, which was typically an imported colour, was slightly less commonly used in Vesilahti’s ryas. The colours of these rugs therefore differ from the blue-and-yellow colour scheme of Eastern Häme and Central Finland. Because plant dyeing produces unique colour results, all ryas are also unique. Bright colours were not introduced to ryas until the end of the 19th century.

The patterns and motifs in Vesilahti’s ryas have originated from the weavers’ imaginations as well as from outside influences, and the rya patterns used seem to indicate that ideas from the latter were happily borrowed. Plant and animal motifs and various heraldic symbols were copied from embroidered pieces favoured by the gentry, in particular.

The oldest of Vesilahti’s ryas often used geometrical themes, such as squares, stripes and zigzag patterns. However, at the end of the 18th century, flowers, vases, animals, people and hearts had already begun appearing in ryas. Looped squares, among other symbols, were also used for good luck. Another fairly common motif was the tree of life, which was believed to bring happiness and prosperity to marriages. Similarly to a cross, it was considered a Christian theme, although the symbol itself had existed since the Sumerian and Assyrian era. The tree of life is also depicted in the parish of Vesilahti’s wedding rya, which was weaved in 1955 but is a copy of a piece dating back to 1802.

Ryas travelled from one parish to another with grooms and brides. Perhaps this is how the tulip motif from Satakunta spread to Vesilahti, too. Even though people tried to produce everything they needed themselves, exported goods from the markets of Narva in Estonia and Turku in Finland, as well as from travelling salesmen were also popular. In addition to new materials and tools, patterns, motifs and beliefs also spread among the weavers. Turkish and Persian rugs and the gentry’s tapestries provided exotic new themes.

Due to the vast number of work hours and amount of wool yarn it takes to make a rya, these textiles were considered very valuable. Often, yarns were dyed at home, either with plant dyes or expensive dyes purchased elsewhere. The older generations, in particular, still wish to make and give valuable pieces of art textile to younger people, for example as housewarming gifts. Up until the 20th century, mothers used to give each of their sons a rya as a gift. The eldest daughter inherited the family’s bridal rya, and the other daughters were given woollen shawls. The bridal rya was a celebratory piece of textile that a woman kept throughout her life, and finally the rya would be used as her burial shroud.

The transmission of the tradition

Currently, no traditions are passed on within families as they used to, and instead local operators, support networks and research on ryas are the primary means of transmitting the tradition. Although Vesilahti still has inhabitants whose families originate there, due to the increased mobility of the population, the majority of the people living in Vesilahti these days are from elsewhere. Therefore, the preservation of the tradition is not self-evident. In Vesilahti, many local types of traditions have always been so strong that they have attracted plenty of newcomers, as well. Vesilahti’s rya tradition has also inspired many designers who live elsewhere.

In 1976, Vesilahti was selected as a research topic on textile tradition for Fredrika Wetterhoff’s Cottage Industry Instructor Institute (HAMK). Out of the 134 wall textiles mapped as part of this study, 87 were ryas. The most important outcome of this research was that in 1978 Vesilahti received its own cottage industry advice centre, which later became known as Vesilahti’s crafts centre or Taito centre, and ever since its foundation, it has actively been working to pass on the rya tradition. Numerous ryas have been weaved at the centre’s facilities, and ryas have been showcased in many exhibitions.

Since the 1990s, the Taito centre has functioned as a rya centre, which provides patterns, materials and training on how to make ryas. Materials are naturally also available at crafts shops. With support from a development project for industries, Vesilahti has created a new, contemporary collection of ryas alongside the traditional ones, and new pieces are constantly being added. New research projects have also been conducted in the 21st century.

Traditional ryas have retained their value and status, but they are not always suited to modern rooms, for one reason or another. Therefore, new ryas have begun to take a modern approach to old motifs related to Vesilahti’s rich history, mythology and other themes, and this has made ryas ever more popular. Tales of a gigantic tree, Sakakuusi, are depicted in at least four ryas. The rya called Palava sydän (‘Burning heart’), designed by Impi Sotavalta, has been called Elinan surma (‘Elina’s death’), according to a folk song from Vesilahti. A rya was also made for the white-tailed deer released into the wild from Laukko Manor in 1934. Similar themes will be available for designers for a long time to come.

The most long-term projects passing on the tradition have included a book describing the history of Vesilahti’s ryas (Aatelisryijy, arkipeite, arvotekstiili) and the rya register on the Municipality of Vesilahti’s website. New entries are constantly made to the register, and it contains pictures of and information on over 200 ryas. Furthermore, the tradition is still being passed on by private weavers.

The future of the tradition

In order to safeguard the tradition, it must hold some sort of timeless significance. However, ryas may take some deciphering as their meaning may be hidden in various ways in their patterns, colours, shapes and history. This means that the traditional appearance is not sacred, which is why ryas can and must evolve – otherwise the continuation of the tradition will be at risk. A constant, albeit a gradual change has been part of Vesilahti’s history before, as well.

The designers and makers of Vesilahti’s ryas, as well as the local Taito centre, have made efforts to adjust to the present and expected future needs. More free-form models have been created alongside the traditional ones with patterns, shapes and materials that meet the more extensive needs of the modern day. As the busiest people will hardly have time to make their own traditional ryas, many miniature models have been designed for them. However, these can be designed at home, as well, weaved and given as birthday or business gifts. Smaller homes are also more likely to have space for smaller ryas. Guidance is available at the Taito centre and from local people who have made several ryas. Perhaps there are still mothers around who teach their daughters how to weave them.

An attempt has also been to connect the ideas of happiness, prosperity and well-being with ryas. It is likely that this tradition will continue within individual families. Ryas can also convey memories. Many of them were probably created in connection to specific events and expectations. A carefully made rya that has taken large amount of work to complete evokes memories the same way as all other symbolic art.

Many of Vesilahti’s ryas are accompanied with stories about events that people cannot or will not forget. One rya is about the destruction of a newly-constructed building, and a bridal rya about the premature death of its owner. One reflects a discord between brothers, another was stolen during a war, and one shows the year when the owner’s grandmother got married.

Owners of ryas often tell old stories like this. In fact, few ryas have no story behind them. A rya with a symbolic meaning is valued, and with it the rya tradition can gain permanent strength. Future generations will probably like to leave a memento to their offspring, as well. A beautiful and long-lasting rya offers excellent means to do so.

The community/communities behind this submission.

Vesilahden Taitokeskus

Vesilahden kunnan ryijyrekisteri

Vesilahden Museoyhdistys

Many individual practitioners

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Arajärvi Kirsti: Vesilahden historia. Hämeenlinna: Arvi A. Karisto Oy, 1985.

Gadd Pehr Adrian: Underrättelse om Färge-Stofters Planteningar I Finland Af Saflor, Krapp och Vau. Åbo, Tryckt hos Directeuren och Kongl Boktryckaren i Stor Förstendömet Finland, Jacob Merckell, Åhr 1760.

Honka-Hallila Helena (toim.): Vesilahti 1346-1996. Jyväskylä: Vesilahden kunta ja Vesilahden seurakunta, 1996.

Hoppu Matti (toim.): Hinsala - kylä Laukon kainalossa. Vesilahti, Vesilahden Hoppu-suku, 2003.

Hoppu Matti (toim.): Vesilahti - tarinoitten ja myyttien pitäjä. Eläkeliiton Vesilahden yhdistys ry, 2006.

Hännikäinen Tuija: Ryijykirja, 1996.

Järvenpää Maarit: Vesilahden seinätekstiilit. Vesilahti-projekti. Fredrika Wetterhoffin Kotiteollisuusopettajaopiston tutkielma, 1977.

Kankkunen Helle, Siippainen Lius: Vesilahti-projekti. Fredrika Wetterhoffin Kotiteollisuusopettajaopiston tutkielma, 1977.

Kylliäinen Mikko: Mitä arkistot kertovat vesilahtelaisista esi-isistämme? Tampereen seudun sukututkimusseura ry:n Vuosikirjassa nro XX:1 (1999), s. 39-45.

Kylliäinen Mikko & Puro Ritva (toim.): Aiwan kowa tapaus. Kirkonvartija Tuomas Tallgrén ja hänen aikakirjansa vuosilta 1795-1837. Jyväskylä, Wesilahti-Seura ja Vesilahden Kunta, 1996.

Lagerstam Liisa: Laukon herra. Gabriel Kurcki (1630-1712). Laukko Historicum, 2008.

Matinolli Eeva: Näin elettiin Vesilahdessa 1762-1900. Käsikirjoitus perukirjatutkimukseen, 2007.

Nytorp Rauno (toim.): Polveilee polut - raikuu rannat. Kertomuksia Palhon ja Vakkalan tienoilta. Palhon Maamiesseura ry, 2006.

Puro Ritva (toim.): Vesilahden seurakunnan rippikirja vuosilta 1688-1694. Vesilahden seudun sukututkimusseuran julkaisuja I, 2006.

Raevuori Yrjö: Laukon omistajia ja vaiheita. Tampere 1963.

Sirelius U.T.: Suomen ryijyt. Tekstiilihistoriallinen tutkimus. Helsinki 1924.

Sopanen Tuomas ja Willberg Leena: Ryijy elää. Helsinki, 2008.

Toikka-Karvonen Annikki: Ryijy. Helsinki, 1971.

Willberg Leena, Rantala Hilkka, Nytorp Eeva: Aatelisryijy, arkipeite, arvotekstiili. Vesilahti kertoo ryijyn tarinaa. Pirkanmaan käsi- ja taideteollisuus, 2008.

Websites

Taitokeskus Vesilahti: http://www.taitopirkanmaa.fi/vesilahdenkasityokeskus

Käsityö verkossa ry https://punomo.npn.fi/kasityo-verkossa-ry/

Vesilahden ryijygalleria: http://www.vesilahti.fi/palvelut/kulttuuritoimi/ryijygalleria/