Workers’ Labour Day on May 1

| Workers’ Labour Day on May 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

May Day, celebrated on 1st of May, and the related traditions are very well known in Finland. Generally, the day is considered the start of spring and the celebration of students and workers.

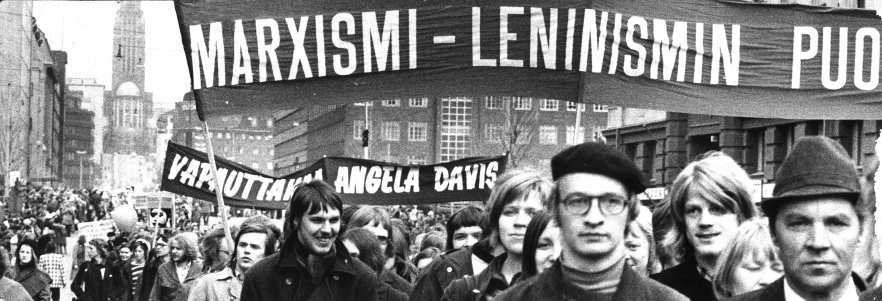

Workers’ Labour Day refers to the celebrations that have evolved over the past 100 years around the activity and traditions of the labour movement. The Workers’ Labour Day, touches the entire nation and is characterised by a heightened sense of democracy, class consciousness and collective power. These themes are reflected in the most important traditions of Workers’ Labour Day festivities, such as May Day parades and political celebrations. Those who fought for their ideology are also commemorated on this day.

Practising of the tradition

Workers’ Labour Day is celebrated in a fairly similar fashion around Finland.

The largest celebrations with the highest number of people take place in the biggest cities and industrial towns.

The day’s programme usually follows a traditional protocol. The May Day morning typically begins with a memorial gathering held in honour of those killed for their ideology. This is followed by a May Day parade, which is also the most impressive part of the celebrations. The majority of the parade’s participants represent labour movement associations, trade unions and political parties. However, the parades are open to all who share the labour movement’s ideals.

The purpose of the parades is to promote the labour movement’s values, social cohesion and collective power. Before the creation of modern media culture, the parades functioned as extremely effective tools to demonstrate public opinion. Parades were used to make demands for social improvements and highlight social problems. Equality, democracy and pacifism have thereby formed the core themes of May Day parades. In order to promote these themes, red flags, banners and shouted slogans are still used during parades.

The course of each parade is carefully planned. Before the parade, the participants arrange themselves in lines according to a prior plan and raise their emblems. Once everything is ready, the lines begin to move along their pre-planned route towards the ultimate May Day celebration venue. The routes are typically fixed, but may also change over time. For example, the traditional route of Helsinki’s May Day parade from the Railway Square to Hakaniemi was changed in 2016, and the parade travelled from Hakaniemi to Kansalaistori square, instead.

The actual Workers’ Labour Day celebration begins after the parade. The highlight of the celebration is the political speech, traditionally given by an active labour movement member, who is known either at a national or a local level. These speeches delve into both current and annually changing themes. In between speeches, there are usually music performances or other cultural entertainment. Due to the fragmented nature of the labour movement, a single town may have several May Day celebrations. For example, the social democrats and the communists will typically hold their own May Day celebrations. However, the celebrations usually share the same structure, regardless of the political views.

On May Day, the workers often hold outdoor concerts and take day trips into nature, among other things. A good example of an event external to the so-called official May Day programme is the Workers’ Song Karaoke event, held annually at the Finnish Labour Museum Werstas in Tampere.

The background and history of the tradition

The earliest records of the Workers’ Labour Day celebrations in Finland date back to the mid-19th century. The traditions that are observed today, however, evolved decades later. The contemporary Workers’ Labour Day celebrations are a mixture of old Scandinavian and Russian festivities celebrating the beginning of summer and the European and American class struggle traditions of the late 19th century.

During the mid-19th century, May Day was not thought of as a workers’ celebration. Up until the late 19th century, it was common for the workers to celebrate the beginning of summer on the first day of May. The celebrations were occasionally rowdy, even violent. For example, as late as in the early 1870s, the factory workers and craftsmen of Tampere used to gather in the town centre for a fight on May Day. The townspeople ultimately grew tired of the annual fighting and began developing other events to take its place. In the 1880s, the May Day celebrations became more peaceful with the introduction of walking tours, concerts and evening entertainment organised for the town’s workers.

The creation of the labour movement’s modern May Day traditions began during fin de siècle. The celebrations became more political when the Second International declared May 1 as the international demonstration day for the workers in 1889. This declaration was made in honour of the workers killed on May Day 1886 by the Chicago police for their participation in a demonstration for eight-hour work days.

The first Workers’ Labour Day in Finland was organised by Helsingin Kirjatyöntekijöiden yhdistys (‘Helsinki’s Printing House Workers’ Trade Union’) in 1890. Five years later, the country’s first joint May Day parade for all workers was organised in Helsinki. The first clearly political May Day parades marched through Helsinki and Tampere in 1898 under the banner of the temperance movement. The parades of 1898 were joined by thousands of people supporting this movement and prohibition. However, the temperance movement quickly died out and by the early 20th century, workers had began to parade for the correction of more extensive social issues.

A defeat in the Finnish Civil War in 1918 reduced the workers’ chances of celebrating Labour Day during the following decades. The victorious side had reservations about the workers’ celebrations. May Day celebrations suffered regular interruptions during the 1920s and 1930s, and for example the Finnish Secret Police had their monitors keep an eye on the Workers’ Labour Day celebrations until at least the early 1930s. The Ministry of the Interior also placed restrictions on the Workers’ Labour Day celebrations: in 1933, the use of red flags and singing certain workers’ songs in public was banned. In the late 1930s, control became less strict, and celebrations could be held more freely.

May Day’s status as the workers’ celebration became more prominent during the 1920s, when the Soviet Union declared the day as the official workers’ day. During the Cold War, the tradition spread to the Central and Eastern European socialist countries. In Finland, too, May Day began to be recognised as the workers’ celebration by the end of World War II. In 1944, Finnish Parliament passed a law that turned May Day into a holiday for workers under certain conditions. Since 1979, May 1 has been celebrated as the Day of Finnish Work, and it has also been granted the status of an official flag day.

The transmission of the tradition

The Workers’ Labour Day traditions have been at their strongest every time the political left has been at its most popular. Especially during the decades following World War II, the May Day celebrations in larger cities saw tens of thousands of attendants. However, the number of people attending May Day parades and celebrations has declined since the late 20th century.

One of the reasons for the decreased interest is the collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing crisis of socialism. The declining numbers may also be the result of the fragmentation of the modern social structures and identities. The growth of the middle class, change in economic structures and increase of temporary jobs have made the concept of ‘worker’ more difficult to define and associate with. For example, the leader of the Left Alliance, Li Andersson, has stated that May Day’s role as the celebration of temporary employees and the underprivileged should be emphasised more.

Even today, the Labour Day traditions of the working class have a central role in the celebrations of May Day. They are passed on by members of the labour movement, other stakeholders and, most importantly, regular people. Recently, the celebration traditions originating from the labour movement have begun to spread among other movements, as well. For example, the roots of the so-called March for Jesus and the anarchists’ May Day demonstrations can be found in the labour movement’s May Day traditions.

The future of the tradition

The line between the internal and external May Day traditions may become even more obscured in the future. What is certain is that some of the labour movement’s May Day traditions will change. Overall, the features of May Day have for a long time been becoming increasingly carnivalistic, which is bound to have an impact on the labour movement’s celebrational culture, as well. This is evident in, for example, how nowadays an increasing amount of popular music can be heard alongside the traditional brass bands and workers’ songs.

On the other hand, some people within the leftist movement have begun to question the significance of the May Day marches for voicing social issues. This is largely due to the increased use of electronic messaging and the internet. However, the importance of the May Day parades and celebrations as a form of expressing social coherence and collective power has simultaneously increased.

Coronavirus broke the May Day tradition in 2020-21, when events had to be canceled and moved to virtual events.

The change in the traditions does not mean the death of old traditions or that the core values of the Workers’ Labour Day have been forgotten. May Day will remain a workers’ celebration far into the future. The significance of May Day traditions that take a stand on social issues may even increase as poverty and inequality also increase.

The community/communities behind this submission

The Finnish Labour Museum Werstas

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Television and radio

MTV Uutislive, Vappu on työväen juhla – missä luuraa työväenliike?.

YLE, Työväen laulut. Martta Salmela-Järvinen muistelee. Yleisradio, 29.4.1968.

Bibliography

Aalto, Satu (toim.), Suuri Perinnekirja. Karisto Oy, Hämeenlinna 1999.

Aatsinki, Ulla, ”Taistelun vuosikymmen – kriittiset toverit 1920-luvulla”. Teoksessa Aatsinki, Ulla, Lampi, Mika & Peltola, Jarmo, Hirmuvallan huolena vankilat ja tuonela, 158–232. Tampere University Press, Tampere 2007.

Halminen, Seppo et al., Lippulinnat Juhla-, vappu- ja mielenosoituskulkueita yli 100-vuotta. Työväen Sivistysliitto TSL ry, Helsinki 2005.

Kirkko-Jaakkola, Kaisa, Simaa, kuorolauluja ja punalippuja Tamperelaisten vapunvietto 1860-luvulta vuoteen 1939. Tampereen kaupungin museolautakunnan julkaisuja 17, Tampereen kaupungin museota ja Pirkanmaan maakuntamuseo, Tampere 1987.

Koivisto, Tuomo, Työt ja tekijät Näkökulmia tamperelaiseen ammatilliseen työväenliikkeeseen 1800-luvulta 2000-luvulle, 490–503. SAK:n Tampereen Paikallisjärjestö ry, Tampere 1999.

Lehtonen, Juhani, U. E., ”Vappu”. Teoksessa Vento, Urpo (toim.), Juhlakirja suomalaiset merkkipäivät, 122–126. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 59, Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, Helsinki 1979.

Pärstinen, Hilja, ”Juomalakkoliikkeestä ja sen merkityksestä”. Teoksessa Työväen kalenteri II 1909, 51–57. Sosialidemokratinen puoluetoimikunta, Helsinki 1908.

Seljavaara, Anu & Kärjä, Päivi (toim.), Juhlat alkakoot! Vuotuisia tapoja ja perinteitä, 92–99. WSOY, Helsinki 2005.