Playing and building the kantele

| Playing and building the kantele | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the national inventory | ||||

|

Practitioners and people who know the tradition well

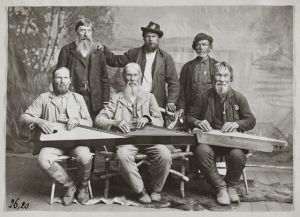

Everyone in Finland has heard of the kantele, a type of zither. This is, above all, due to the fact that it plays a crucial role in the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala. In fact, the kantele became known as the national instrument thanks to the publication of The Kalevala and the rise of national romanticism. The kantele in The Kalevala has five strings, and this early form of the instrument is the best known. However, most people are also familiar with the kantele’s later development into the present-day 40-string instrument. For many people, the kantele is simply a national symbol that is sung about in spiritual and secular songs, but most people also know it as an instrument that is played in all genres of music.

Kantele players can be found all over Finland. There are organised activities led by official educational institutions as well as associations such as Kanteleliitto ry (the Kantele Union) and Kanteleensoiton Opettajat ry (the Association of Kantele Teachers). On the other hand, there are also private activities, as the kantele is still a very personal instrument for many people, in the centuries-old way.

The kantele can be played solo, as accompaniment to songs and in kantele ensembles and all other types of ensembles. In many schools, the kantele is played during music lessons and celebrations. Playing the kantele solo is most likely still the most common way. The players represent all age groups and come from all kinds of backgrounds, ranging from young children in music play school to enthusiasts at adult education centres and people playing at home, as well as from music school students to doctoral degree students of fine arts at the University of the Arts Helsinki. Some of these doctoral degree students study classical music, while others study folk music. There are dozens of professional kantele players.

Kanteles are being built in different parts of the country. Many people build a few kanteles as a hobby. In many schools and educational institutions, they are made on crafts courses. Additionally, there are a few professional kantele builders operating around the country. They build all types of traditional instruments with 5 to 40 strings while also developing their own designs based on tradition.

There is a great deal of research being conducted and published on the kantele in Finland. This research examines, above all, the history of the instrument’s structure, builders, players and music but also the present day. The Finnish Kantele Museum operates in Palokka, Jyväskylä.

Practising of the tradition

One of the most remarkable characteristics of the Finnish kantele is the fact that its thousand-year history continues on with vigour and vitality today. There are kanteles of all sizes and appearances, ranging from five strings to 40 strings, and all the most important historical kantele types are represented among them. Kanteles are built both by imitating museum instruments and according to the builder’s own ideas.

The kantele has been and continues to be used to play music from all eras of the history of Finnish music, from the most archaic to the most modern. The long-standing aesthetics of the oldest music were brought forth by the 5–15-string kantele. In recent decades, many types of music activities have been launched based on these aesthetics. The era of folk music still lives on in a few types of kanteles, such as the kanteles of Perhonjokilaakso, Saarijärvi and Haapavesi, as well as the music played on them. Classical music has been played on the kantele since the late 19th century, and music intended specifically for the kantele has also been composed since the beginning. In recent decades, these compositions have also included very modern pieces. Additionally, the kantele is played in popular music, and popular music has been composed for it.

Kanteles share common structural characteristics, but there are still numerous types of kanteles. The same applies to kantele playstyles: many people use traditional playing techniques and styles, but there are even more people who have developed their own style. The kantele has been in a transition period for almost two hundred years, both as an instrument and in terms of music, and there are no signs of the situation stabilising.

One of the characteristics of this diversity is the fact that the kantele was originally played so that the shortest string was closest to the player. Towards the end of the 19th century, the classical music circles developed a playstyle in which the longest string of the kantele is closest to the player. Today, both traditions continue to thrive and evolve.

The kantele and the kantele tradition are also present in Finnish culture in the form of poems, songs and tales. Particularly worth mentioning are the poems in The Kalevala about Väinämöinen as the builder and player of the first kantele as well as spiritual hymns that describe the heavenly kantele and heavenly kantele playing.

Kanteleliitto ry is an association for kantele players and builders. It is a rare type of instrument organisation in the sense that the members of the association and its governing bodies represent all the different trends. The union organises international kantele competitions, presents recognition awards and publishes the Kantele magazine.

In many ways, the kantele is still a mystery as an instrument. Kantele researchers test the characteristics of museum kanteles and attempt to reconstruct the sound of ancient instruments. The changes that have taken place in the structure and instrumental characteristics of the kantele are a subject of research. Composers and players revive old and search for new playing techniques.

The background and history of the tradition

The age of the kantele is not known exactly, but most experts estimate that it is a few thousand years old. In other words, as an instrument played by Finns, it is several hundred years older than the bowed jouhikantele, or jouhikko. The traditional area in which the kantele is played covers the areas east and north of the Baltic Sea, which include Finland, Karelia, Vepsia, Ingria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Northwest Russia. In this area, the kantele has common routes that go back thousands of years, and the oldest kanteles, which are carved from a single tree, are close relatives of each other. Of course, differences already existed in the early days, but when kanteles carved from a single tree were replaced by kanteles built from boards and when the number of strings increased at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, the kantele evolved in different directions in different areas. Due to this, the Finnish kantele also has its own history, despite its common roots. On the other hand, it is understandable that kantele researchers and players have been engaging in active international cooperation for decades.

When, in the 19th century, Finnish builders began to build kanteles from boards, instead of carving them from trees, all builders had to come up with their own solutions for the new instrument’s structure, which resulted in numerous different types of structures. Elias Lönnrot, who turned the kantele into the Finnish national instrument with the poems in his epic, The Kalevala, and who was a kantele player himself, was already building large, original board kanteles in the 1840s, and he also built chromatic kanteles slightly later on. However, kanteles with more than 30 strings did not become consolidated until the beginning of the 20th century. New structural elements invented around that time included the damping board, the long, curved side and a mechanism that made it possible to switch from one key to another. New playing techniques and new types of music were also created at the same time.

The status of the kantele weakened in the 20th century, but the efforts started in the 1970s to revive the tradition succeeded beyond expectations. Many successful projects were launched at the time, including the founding of Kanteleliitto, training of kantele builders, the introduction of the five-string kantele as a school music instrument and the incorporation of the kantele into the curriculum of music schools.

The transmission of the tradition

The upholding and passing on of the kantele tradition is provided with a strong foundation by the fact that this work is carried out in conjunction with kantele teaching at all levels of music education. Teachers are well-versed in the history of the kantele and seek to both preserve and develop the characteristics of the tradition.

A couple of local and regional building and playing styles still live on. Some of them have achieved wider popularity and spread nationwide. Thanks to training, many young players are ambitious developers of their own style. They are simultaneously a guarantee that the kantele will retain its diversity.

The tradition is also being passed on with the help of a wide variety of course activities. Publications are even more important. Kantele music is being published as recordings and sheet music for all genres of music. The Kantele magazine published by Kanteleliitto provides information on the history, present and future of the kantele in great detail. The magazine’s forty annual volumes themselves form a rich documentation on the efforts made to revive the kantele.

The future of the tradition

The future of the Finnish kantele seems to be very secure. Its status has only strengthened and grown more diverse in recent decades. Historical instruments and their music are being revived. On the one hand, instrument builders are coming up with new structural characteristics for the kantele that make it increasingly easy to use in all genres of music. This is particularly visible in the development of the electronic amplification of the sound of the kantele. On the other hand, there are a great number of kantele artists who want to play acoustically, without a sound reinforcement system.

The community/communities behind this submission

Sibelius-Akatemian kansanmusiikin aineryhmä

Suomen Kantelemuseo, Jyväskylä

Bibliography and links to external sources of information

Video links

YouTube: Arja Kastinen playing 10- ja 14-string kanteles. "Musiikin muisti" -serie pt. 6.

YouTube: Pauliina Syrjälä plays kantele by strumming the unstopped strings. "Musiikin muisti" -serie pt. 7.

Literature

Asplund, Anneli: Kantele. The Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki. 1983.

Dahlblom, Kari ja Tuula: Keski-Suomen kantele. 2011.

Jalkanen, Pekka, Laitinen, Heikki ja Tenhunen, Anna-Liisa: Kantele. The Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki. 2010.

Kastinen, Arja: Itäisen Suomen ja Karjalan kanteleista 1800-luvun käsikirjoituksissa. Temps, Pöytyä. 2009.

Kastinen, Arja, Nieminen, Rauno ja Tenhunen, Anna-Liisa: Kizavirzi. Karjalaisesta kanteleperinteestä 1900-luvun alussa. Temps, Pöytyä. 2013.

Laitinen, Heikki: Matkoja musiikkiin 1800-luvun Suomessa. Tampere University Press. 2003.

Leisiö, Timo: Alussa oli laulu. Tampere. 2006.

Nieminen, Rauno, Väänänen, Timo ja Rossander Meri-Anna: Kantele eläväksi. Museum of Nurmes. 2011.

Saha, Hannu: Kansanmusiikin tyyli ja muuntelu. The Finnish Folk Music Institute, Kaustinen. 1996.

Smolander-Hauvonen, Annikki: Paul Salminen, suomalaisen konserttikanteleen ja soittotekniikan kehittäjä. Sibelius-Academy. 1998.